Culture and communication

Listen by the lake: engaging the public with sound

A century ago in the 1920s, when the University of Nottingham was first establishing its home above the peace and quiet of Highfields Park, Britain was in the grip of an audio revolution. Radio broadcasting had just begun, and telephones were replacing letters as the communication norm. Fast forward to the 2020s, and a new digital audio revolution is in full swing. Smartphones demand our listening attention as well as our visual attention as we stream music, swap voice messages, and listen to podcasts. Digital audio is everywhere, from viral TikToks to video games and from background music in shops to the privacy of our bedrooms, where an industry of sleep-inducing sounds is booming. In this world of ubiquitous sound, it’s more important than ever to engage the public with opportunities to listen differently.

Listen by the Lake is a new public engagement programme led by the Institute for Policy and Engagement at the University of Nottingham. Four listening posts have been placed around Highfields Park offering visitors the chance to hear from the university’s researchers. Each post features the voice of a researcher talking about their work as well as audio relating to their project. Why put these sounds in a park rather than on a podcast? Well, the Institute for Policy and Engagement already has a podcast. Listen by the Lake sets out to do something different. The listening posts offer chance encounters with ideas and sounds that usually live behind closed doors on the university’s campus. Highfields Park is a public place, where anyone can visit. At the push of a button, listeners can hear about distant galaxies or the hidden life of algae- just two of the topics to feature so far. Public parks have always offered respite from the sights and sounds beyond their boundaries. Along with the rustle of the wind, the lapping of the lake, and the tweets of local birdlife, park visitors can now hear snapshots of university life, too.

Sound-based public engagement works best when it involves taking listeners beyond their usual listening habits. Sound walking is perhaps the most established method of doing this: it involves asking public groups to walk through environments paying close attention to what they hear. The idea is that we usually block out much of the sound around us. Some organisations use online sound maps to spark this kind of engagement. In this approach, public audiences are invited to record sounds in their everyday environments and upload them to an online map, as in the Essex Sounds project run by the Essex Record Office. The purpose here is to cause people to listen more closely to their surroundings to gain a stronger sense of place. Other sound map projects aim to help people think about how urban environments should sound, for example in relation to how unwanted noise is managed. At Lund University, sound artists are invited to create works for a specially designed ‘sound bench,’ a conventional outdoor bench with built-in loudspeakers. The latest piece, ‘Metamorphosis’ by Jacob Kirkegaard, uses the sounds of butterfly wings to engage listeners in the sounding dimensions of the climate crisis.

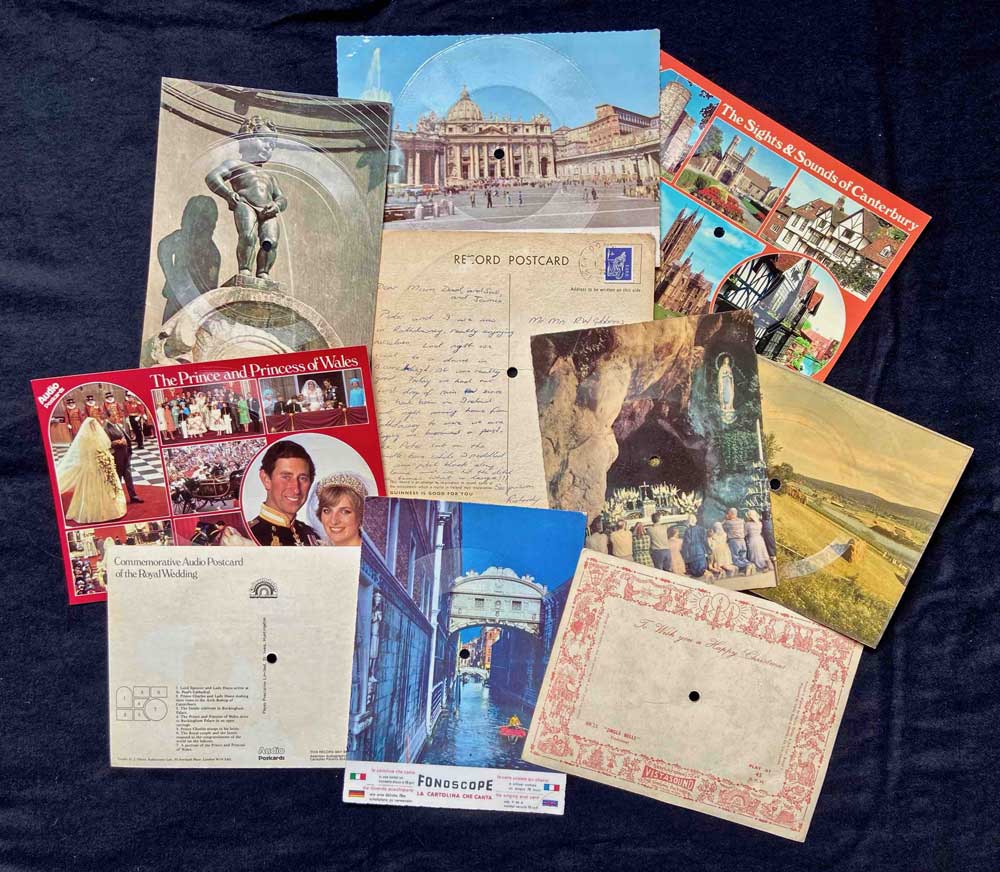

In December 2021 the University of Nottingham’s Faculty of Arts takes over Listen by the Lake for a special focus on arts and humanities research. Visitors to Highfields Park will be able to hear about Jai McKenzie’s research on marginalised families, Hannah O’Regan’s research on bears in early modern England, and composer Elizabeth Kelly’s work. My own project about the history of sound postcards also features on one of the listening posts. From the beginning of the twentieth century up until the 1970s, you could buy postcards with an embedded record to play at home on your record player. Some of these allowed you to record your own voice message. Others contained a popular song, or a sound connected to the picture on the postcard. I worked with a public group during the first coronavirus lockdown to re-create a new set of sound postcards to spur reflection on how our relationship with audio media has changed over time. Some of the sounds recorded by the group for their postcards will feature at Listen by the Lake.

Using listening-based activities to engage the public is especially important where sound itself is the subject of engagement. Over the last few years, I have been working with the National Science and Media Museum on an AHRC-funded project called ‘Sonic Futures’ about how to exhibit sound technologies, such as sound postcards, in museums. In this context, showing visitors a sound postcard, or a gramophone set, or a radio receiver, or a synthesiser, is not enough, because these objects were meant to be heard as well as seen. The Sonic Futures project designed a series of sound-making activities, such as sound postcard making, that brought sound technologies to life through sound. In the future, I hope that museums will be thought of as places for listening as well looking, and spaces where public listening cultures form. Listen by the Lake can do the same thing at the University of Nottingham by embracing a new listening public in the park.

James Mansell

James Mansell is an Associate Professor in Cultural Studies, Faculty of Arts