By Daniel H. Mutibwa, Amanda Hanton, Brian Kennedy, Suzie Parr, Louise Sharples and Mandeep Kaur

Showcasing creative approaches to developing audience data strategies in the cultural and creative sectors

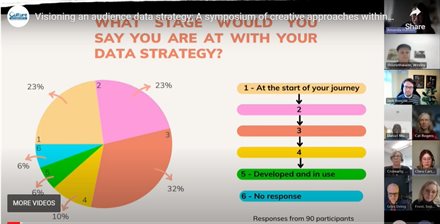

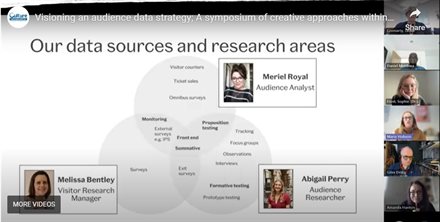

A screenshot capturing the different stages at which event attendees are at on the audience data strategy development journeys

A screenshot capturing the different stages at which event attendees are at on the audience data strategy development journeys

We were very excited to host a symposium that showcased creative approaches to developing audience data strategies in the cultural and creative sectors in England and Scotland on Wednesday 6 March 2024. This two-and-a-half-hour event featured highly informative presentations from a range of speakers who shared their respective journeys to date of developing their audience data strategies. Amanda Hanton steered us deftly through the event — starting by introducing the programme, outlining the ambition of the Libraries and Heritage Services / Culture Leicestershire at Leicestershire County Council (LCC) to develop an audience data strategy, and offering the following useful context. Of the 90 participants who signed up to attend this event, 6% indicated they had a data strategy that was fully developed and in use; 23% noted they were at the beginning of that journey; and 23% reported they were a little bit farther down the journey. Clearly, the scene was set to learn and share from one another productively in very much the same way that we did during the Visioning a Creative and Cultural County Conference and the Cultural Strategy Symposium.

In his introductory remarks, Daniel H. Mutibwa provided a brief background to the Visioning a Creative and Cultural County (VCCC) research-policy impact project that is laying the foundation for the development of LCC’s Cultural Strategy and supporting the creation of LCC’s audience data strategy. Daniel noted that the public engagement events delivered by VCCC, just like the Audience Data Strategy Symposium, had brought together local, regional, and national stakeholders from policymaking, business, industry, and Voluntary, Community and Social Enterprise (VCSE) sectors to share learning on deploying cultural and heritage assets and data to improve productivity, support capacity-building, and develop sector-wide resilience against the backdrop of persisting austerity and a wider, volatile economic climate.

Developing an effective audience data strategy is a balancing act

Amanda then invited speakers to deliver their presentations one after the other. Jack Roscoe (Tech Champion for Audience Data Collection and Evaluation, Digital Culture Network (DCN)) spoke first. He began by explaining that DCN’s remit is to develop and increase the digital skills and maturity of the creative and cultural sectors in England. DCN does this by giving completely free, unlimited, one-to-one support and advice directly to organisations and individuals. Jack explained further that DCN’s support package ranges from assistance with websites and social media to digital content such as videos and podcasts to marketing strategies to email and communications to Search Engine Optimisation (SEO) and audience research to e-commerce accessibility to Customer Relationship Management (CRM) and ticketing. Jack then shared his understanding of what an audience data strategy looks like — starting with what it is not. To Jack, it is not about data that cover aspects relating to IT, privacy, and GDPR guidelines. Rather, it is about how tools, platforms, processes, and structures are deployed effectively to fulfil set audience goals. In Jack’s understanding, a good audience data strategy is about leveraging tools, platforms, processes, and structures to efficiently capture data and make those data available, comprehensible, and useful for people in an organisation.

Jack Roscoe on what an effective audience data strategy looks like

Jack Roscoe on what an effective audience data strategy looks like

In attempting to achieve this overarching objective, according to Jack, several key goals need to be balanced to help relieve organisations of pressure in terms of what an audience data strategy can realistically achieve. For instance, whilst managing expectations, meeting requirements, investing in building up knowledge about audiences, and adopting data-driven decisions are all valuable goals of an audience data strategy — they also compete for organisations’ time and resources. This calls for a balancing act. Most public cultural and heritage organisations are required to submit a minimum level of audience data to funders.

For National Portfolio Organisations (NPO), for example, this tends to include data collected from mandatory audience surveys, attendance at events, and ticketing information among other sources. Beyond this mandatory exercise, organisations can benefit greatly from collecting data that help them understand their current audiences — including how people came to the organisation, how they discovered the organisation, and what motivated them to come along.

Audience data can also be useful when evaluating what people think is good about the work that the organisation does — and how that work could be improved. Data can point organisations in the direction of potential new audiences and how to reach them. Collection of the right data can helpfully inform the process of segmentation whereby organisations split audiences into distinct groups to better analyse and understand them microscopically. Organisations that invest time and effort in this exercise develop good knowledge of their audiences which, in turn, enables them to communicate and interact with their audiences effectively. In Jack’s view, this can be powerful when tied effectively to an organisation’s mission and goals — including where the organisation sees audiences sitting within its remit.

Cultivating the right mindset: Asking the right questions and collecting the right data from the right places

Jack noted that sources of audience data can vary — ranging from sets of documents or huge spreadsheets to audience survey responses to interview and research material gathered to digital data from websites, emails, and marketing channels to platforms and how they integrate and talk to each other to reports and dashboard information to standardised processes followed by staff within organisations. In Jack’s experience, how these varied sources of information are mined for data determines the efficacy of an audience data strategy. Equally efficacious and vitally important is not only how audience data are collected, processed, displayed, and analysed, but also a matter of mindset. By mindset, Jack meant the significance of developing the attitude to prioritise key data that contribute to triggering productive conversations and good practice, and ultimately, to organisational change. Effecting cultural and organisational change in this way, Jack asserted, is about making audience data available, contextualising and highlighting those data for staff across the organisation in ways that spark discussion and ideas and help produce insight. The key point here is that organisations need to be very methodical and strategic in the way they approach and engage with audience data — if they are to reap the widest possible benefits from those data.

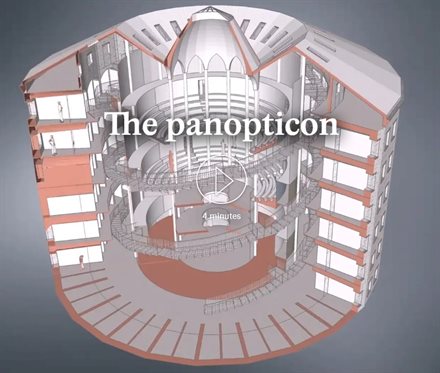

A graphical illustration of the panopticon © Aeon

A graphical illustration of the panopticon © Aeon

Appropriating the concept of the panopticon (i.e., maximum observation and maximum visibility intended to achieve maximum control) propounded by the English philosopher, jurist and social reformer — Jeremy Bentham, Jack suggested that organisations taking a methodical and strategic approach to engagement with audience data refrain from maximum observation of their audiences and indiscriminate collection of data — data that capture every interaction and touch point with their audiences.

Those organisations understand that practices such as attempts at surveying every member of the audience or asking audiences huge amounts of questions at every opportunity and about every part of the organisation’s offer are futile. In part, this is because organisations generally have limited capacity in terms of time and resources. More importantly, many data points or audience touch points generally do not necessarily provide useful information. The more effective and sustainable approach that methodical and strategically thinking organisations take, Jack observed, is to ask a few smart (but right) questions and to collect the right data from the right places.

In doing so, such organisations continually remind themselves of what their mission is and how they work towards fulfilling that mission. Proceeding this way helps organisations filter out all the data that are not needed — leaving the focus on what really matters. One aspect that matters is what the data tell an organisation, and how that organisation then marshals those data to act and foster change.

Jack helpfully discussed the four different formats that characterise audience data. First, descriptive data that tell organisations what happened. Second, diagnostic data that tell organisations why things happened. Third, predictive data that tell organisations what might happen in the future. Lastly, prescriptive data that tell organisations how to influence things or make things happen. To organise and manage these sets of data efficiently, organisations can apply a marketing funnel — understood as a process that outlines the journey that audiences undertake with organisations. This typically starts with becoming aware of an organisation through visiting that organisation’s website or social media platforms. It may then progress to a first interaction with the organisation through signing up to that organisation’s newsletter before going on to engage with an offer. The journey may involve maintenance of contact — part of which may prompt the organisation to induce future interaction. Jack was keen to stress that the approach to engagement with an audience data strategy discussed so far can be messy in practice owing to a few challenges within organisations: interdepartmental politics, some staff not buying into the mindset described earlier, and the failure to get the approach (and elements of it) right at the first attempt. Be that as it may, there is one key point to take away. If audience data point an organisation to what it should be prioritising in its day-to-day work in alignment with its mission, then the likelihood is greater that staff and teams across that organisation will become crucially invested in contributing useful data to their organisation’s systems and following agreed processes because people can see the results and the value of proceeding this way. This sums up what a meaningful audience data strategy is about — from Jack’s perspective.

Better to do a few things well than a lot of things badly

This was followed by the presentation from Wesley Thistlethwaite (Insight and Analysis Manager, National Museums Liverpool) who structured his talk around three key points, namely useful, creative, and influential. For Wesley, a useful audience data strategy is one whose data is best thought of as insights. This echoed a point made in the preceding presentation by Jack that referred to the production of insight as an integral part of an effective audience data strategy. Insight, Wesley explained, is a lens through which organisations can find things out, contextualise them, and discover what they need through mapping out the data they collect. To succeed at this, organisations need to ask questions that are imperative to their remit, embrace creative ways of gathering the data needed to answer those questions effectively, and embed the findings in their work. In proceeding this way, organisations take a systematic approach — finding along the way that it is better to do a few things well than a lot of things badly. Wesley offered an interesting analogy to illustrate the significance of usefulness in relation to collecting data. He narrated how he was inspired by Deliveroo — the online food delivery company. Deliveroo has a star rating service that customers can evaluate with a single click following delivery. However, many customers do not bother rating their experience following the transaction. Wesley asked why the rating exercise should not be requested before the transaction?

Wesley Thistlethwaite on an audience data strategy charactertised by usefulness, creativity, and influence

Wesley Thistlethwaite on an audience data strategy charactertised by usefulness, creativity, and influence

This question prompted Wesley to apply this logic to the setting of the theatre organisation where he worked at the time. Questions about ethnic background were posed to ticket buyers before payment because finding out about this information had been made an organisational priority. The result, Wesley recounted, saw an increase of up to 60% of new ticket buyers providing information about their ethnicity, something that gave the theatre a much better understanding of its audience demographics than the few people that would have filled out the organisation’s surveys.

Here, this theatre organisation collected ethnicity-related data through its box office system meaning the data went directly into the organisation’s centralised CRM system. A custom report was generated. Ethnicity data was also shown on automated post-performance reports which were routinely used in meetings. In turn, meeting conversations formed part of everyday discussion across the organisation. This aligned well with Jack’s understanding earlier of what an effective audience data strategy should aim to achieve: to leverage tools, platforms, processes, and structures to efficiently capture data and make that data available, comprehensible, and useful for staff across an organisation.

Thinking of data as an organisation’s muse and understanding the importance of influence

In terms of what is creative about an audience data strategy, Wesley made several interesting points. He questioned several common perceptions that (1) data-led or data-informed thinking stifles creativity, (2) data always look backwards which hinders forward-thinking, and (3) data discourage experimentation and innovation. Just because creativity is sometimes associated with features such as being sudden, unorganised, and unplanned does not mean it has little to offer data-driven thinking and related processes. Far from it, organisations should view data as their muse, especially if — as we have already seen above — one of the overarching objectives of engaging with data is the production of insight. To Wesley, insight itself is creative because it matches up various findings to pull together a truthful narrative in the same way that artists match up experience together to find a deeper meaning and truth. So — data are used to fuel insight, insight is about discovery, and the combination of data and insight in this way is itself a creative process that limits risks. This is particularly important when considering the risk-averse environment within which public cultural and heritage organisations operate.

Wesley added that data and insight on their own are not enough. This is because the full, truthful picture painted by data, and from which insight is generated, may be susceptible to being ignored by those in positions of authority in organisations. One reason for this, Wesley explained, is that the emergent picture may not fit the narrative that senior management may want to craft. Another reason is that an organisation may be sceptical about the validity of data, and by extension, the insight derived. In instances such as this, insight means nothing without influence. Influence here is understood as the capability to make change happen based on what data and insight are telling an organisation. The key point to take away from this is that staff within an organisation tasked with generating insight can benefit from developing an ability to (1) use data and insight to tell a story in an accessible and engaging way that resonates with others, (2) identify colleagues with soft power across the organisation to continuously brief on emergent insights and their value and to potentially use those colleagues as ambassadors to help spread the word — as it were, and (3) grow the qualities of assertiveness and confidence — especially in situations where the findings from insight can be challenging for the organisation. Also, staff should be prepared to be challenged on the findings put forward.

Adopting an audience-led approach to programming, balancing audience needs, and the value of audience segmentation

Jackie Cromarty presents on the comprehensive audience data work undertaken by the National Library of Scotland so far

Jackie Cromarty presents on the comprehensive audience data work undertaken by the National Library of Scotland so far

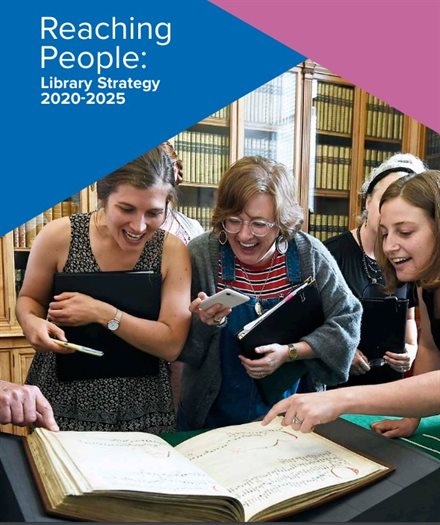

Up next was the presentation from Jackie Cromarty (Director of Engagement, National Library of Scotland) who talked about the audience development journey of her organisation. Henceforth abbreviated to NLS, Jackie described this reference-only library as a free public service with around 50,000 active members at any given time and a busy programme of exhibitions and events that attracts around 150,000 people every year. Founded in 1925 — though technically in existence since 1682 as the Faculty of Advocates Library, NLS will be celebrating its centenary in 2025. As the organisation approaches this milestone, NLS is being guided by the Reaching People: Library Strategy 2020-2025.

That Strategy foregrounds taking an audience-led approach to the development and delivery of all NLS services and cultural experiences, with a particular emphasis on creating great experiences for people and connecting people with collections. While taking this approach is undoubtedly desirable, Jackie intimated that NLS had faced barriers in its execution initially.

One such barrier was that NLS had no history of data collection. Another barrier was that the organisation had little audience research beyond occasional audience surveys. Yet another barrier was that NLS had neither a team or unit that generated insight nor existing staff assigned to this task.This set of circumstances led the organisation to commission the Audience Agency as an external agency to deliver a two-year audience development programme geared towards producing a roadmap to help realise the goals outlined in the Reaching People: Library Strategy. Among other things, this has produced work that is helping NLS to (1) better understand its current audiences, (2) adopt a more audience-led approach to event programming as opposed to a collections-driven one, and (3) balance the needs of the organisation’s audiences. Proceeding this way has been imperative considering that NLS is 90% publicly funded and, as such, has had to reflect relevance and value to a wide range of people.

Jackie explained that two key factors have been at the centre of this organisational transformation, namely staff consultation and training, and (2) the adoption of strategic practice — including leveraging audience segmentation to achieve set audience goals. Not only have NLS staff been brought on board to proactively shape thinking and practice on and around audience development, but staff have also been trained in the application of audience segmentation.

The cover page of the Reaching People: Library Strategy 2020-2025

The cover page of the Reaching People: Library Strategy 2020-2025

In doing so, this has shifted the focus away from a reliance on typically unhelpful or assumptive stereotypes about audiences to working intently with actual audience behaviours and interests. With this has come the use of uniform terminology when engaging with audiences across the organisation.

The benefits of using audience segmentation as a key tool range from identifying audience types to generating key information about those audience types to drilling down that key information into the smallest elements possible to provide useful granular detail to ensuring use of a shared language for purposes of consistency across the board.

To this end, Jackie noted, the organisation has produced an audience segmentation toolkit for staff working in key areas such as public programming, visitor services, reader services, and curatorial services to use as a shorthand for all their work. For illustration, Jackie narrated how the audience segmentation toolkit is being used to think about the kinds of activities that NLS wants to programme going forward.

Cases in point include a major exhibition on ‘Renaissance in Scotland’ planned for late 2024 and the programming of ‘Centenary Stories’ during the centenary year in 2025. In the planning, design, and delivery of both events, the focus and thinking of audiences will feature prominently at various stages.

Leveraging data for transparency, impact generation, and the preservation of legacy

The next presentation was from Giles Dring and Michelle Brook (both freelance data consultants) who spoke about the critical role that data, particularly open data, played during the LEEDS 2023 Year of Culture project. Giles provided some very useful contextual background information which conveyed that this event sprang to life initially as a bid put forward by the city of Leeds for the European City of Culture back in 2016. Following BREXIT, however, the bid was withdrawn but the city decided to go ahead with the event after some funding from Leeds City Council, the National Lottery, and other sources was secured. Working with Leeds Culture Trust Limited which administered the LEEDS 2023 Year of Culture project and an organisation called Open Innovations that supported the Trust with data-related work, Giles and Michelle collected, presented, and visualised event-related data on the LEEDS 2023 Data Microsite with the overarching objectives to foster transparency, generate impact, and preserve the legacy of the event. The Microsite was designed as an extension of the main LEEDS 2023 Year of Culture project website. Giles walked attendees through the very interesting and practical approach taken to achieve those objectives — noting that work started off initially with publishing small amounts of data which were gradually built upon with more data as events developed and activities happened. The fact that data were made live on the Microsite and rendered visible to the public meant that a lot of time and effort were invested in getting the different formats of visualisation right. This involved making several attempts until the mark was hit — so to speak. A key takeaway message here was that it is important to experiment with things on the understanding that we do not always get things right at first attempt.

Giles Dring and Michelle talk about how they built the LEEDS 2023 Year of Culture data microsite

Giles Dring and Michelle talk about how they built the LEEDS 2023 Year of Culture data microsite

Giles explained that transparency was reflected in the ways that the data published on the Microsite was visualised to capture what was happening in real time. Taking the opening performance as an example, Giles recounted how there was uncertainty about whether or not that performance would be successful. The audacity and openness to publish data relating to that performance despite unpredictability in and of itself became a talking point which effectively relayed the spirit of the LEEDS 2023 Year of Culture project. This paved the way for the use of real-time data to make urgent decisions regarding programming and reallocation of ticket ballots among other things.

Publishing content for public use necessitates use of language and terminology in ways that enable people to understand and interpret that content as intended. This principle was applied in this case — allowing users and the public not only to comprehend data, but also drill down into it.

For instance, users and the public could — and still can — access the exact number of events that the LEEDS 2023 Year of Culture project held per month. Events delivered by partners or in partnership with other stakeholders per month can also be accessed separately — providing a level of granularity that can support deeper and meaningful analysis and insight. It is for this reason that the Microsite data came to inform key operations. For instance, data compiled from media coverage informed communications and marketing operations. Giles spoke of how the Director of Communications at Leeds Culture Trust Limited used these data for presentations to Leeds City Council and other stakeholders as part of the routine task of providing critical and timely updates. The data were also used to inform the evaluation framework of the LEEDS 2023 Year of Culture project — although that framework was not intended to replace the evaluation report. At the time of Giles’ presentation, the evaluation report was under production by the Audience Agency which had been commissioned to undertake this piece of work.

The enormous amounts of data published on the Microsite were extracted from operational systems ranging from ticketing systems to volunteer management systems to online forms to ad hoc spreadsheets to various databases. Where data included personal information, this was either redacted or presented differently wherever possible in alignment with GDPR. For example, postcode information was converted to wards. The extraction of data from different sources was made possible using a range of free services. Giles concluded the presentation with the following takeaways. First, it can be helpful to start small. Second, developing the ability to do a lot with little can pay dividends. Third — and reiterating a point Wesley had made earlier, it is important to embrace readiness to engage in challenging conversations about what data might or might not mean. Lastly — and again echoing yet another point that had been made early on by Wesley, it is crucial to be prepared to influence and shape the understanding of data and leverage the insight derived from it to foster transformation.

The importance of securing staff buy-in, viewing audience-related issues as requiring a sector-wide approach, and making audiences everyone’s business across the organisation

Beth Bryan (Audience Strategy Lead, Barbican and Chair, Visitor Studies Group (VSG)) presented next on strategy development at the Barbican amid organisational change. Having found itself being confronted with serious allegations of institutional racism in the Barbican Stories in 2021, the organisation launched a period of significant transformation during which it thought carefully about what it is, what it wants to be, who it wants to engage, and how it wants to do that. To address these questions meaningfully, according to Beth, the organisation developed a strategy over a nine-month period. Taking that length of time was deliberate because it (1) considered the evolving organisational framework that needed to be tapped into, (2) met available resources and capacity needs, considering that no appropriate staff were available to undertake this task, (3) involved extensive staff consultation in a variety of formats to secure buy-in, thereby taking account of the magnitude of cultural change that was happening, and (4) helped to push against a siloed mentality — relaying the important message that independent units across the organisation can neither deliver alone nor achieve success on their own. Beth revealed that not all staff agreed that the organisation needed to change. One third of staff were resistant, another third felt they saw value in organisational change but indicated they needed to support to help implement that change, and yet another third bought into the change almost immediately. Against this backdrop, it was vitally important that senior leadership employed objectivity in painting a clear picture of the circumstances in which the organisation found itself, why the organisation needed to change, and what support would need to be put in place to help staff contribute to the much-needed transformation.

Beth Bryan on audience strategy development amid major structural changes at the Barbican

Beth Bryan on audience strategy development amid major structural changes at the Barbican

In addition to tackling problems relating to the internal structure of the organisation, attention was also directed towards how the organisation interacted with its audiences. It became clear to the organisation that the audience-related issues it was facing were not unique to the Barbican but prevalent across the arts, cultural, and creative industries sector. As a starting point for addressing the identified issues, the organisation applied a ‘competencies framework’ encompassing six categories: (1) data and insights which capture the audience voice and knowledge about the audiences, (2) storytelling which captures how the organisation communicates and interacts with its audiences, (3) service delivery and what audiences make of it, (4) leadership in relation to how the organisation is run, (5) culture — including the nature of roles and how staff interact with one another across the organisation, and (6) operating model which sets out how the organisation is structured and functions. An assessment of where the organisation is currently at using this framework has pointed to knowledge gaps that are being addressed. Examples of some of the concrete steps being taken — several of which echo some of the approaches discussed by earlier speakers — include the following.

The organisation is working to retain existing audiences while bringing in new ones and ensuring that programming speaks to both old and new. In doing so, the principle of starting small and seeing how progress shapes up is being embraced. A strategic approach is being taken to collect only data that focus on what the organisation wants to measure and understand about its audiences as opposed to gathering data about everything relating to those audiences. The ultimate goal is to find out what audiences want and to work with them to deliver that. This is all being undertaken within the context of what Beth called a ‘values-led, data-informed decision-making’ approach that underpins the organisation’s new strategy. At the heart of this are five drivers: (1) becoming sustainable by refraining from solely chasing box office figures, (2) working with and for audiences in inclusive ways, (3) embracing connectedness by breaking down siloes internally while building relationships externally across the sector, (4) adopting joyfulness to inform the delivery of positive experiences, and (5) being audacious in designing and delivering relevant and civically engaged programming of the kind that connects with the issues that audiences care about.

Whilst this approach is ensuring that the organisation is heading in the direction it needs to, there is also acknowledgment that the current organisational structure can sometimes be more constraining than enabling and that tight resources can be limiting in terms of how much change can or cannot be supported and implemented. That said, positivity and resourcefulness have clearly emerged from this — helping the organisation to rethink how best to reconfigure its set-up and to reallocate its tight resources on the understanding that ‘audiences should be everyone’s business’ — in Beth’s words. The overall experience of navigating organisational change thus far has taught the Barbican three key aspects, namely managing expectations carefully, being very clear about priorities, and avoiding the temptation of running before mastering how to walk.

Slow, crisis-induced change and the organisational learning paradox for cultural and museum organisations

Dr Marie Hobson shares how organisational learning theory has informed a new approach to engaging with audience data work at the V&A

Dr Marie Hobson shares how organisational learning theory has informed a new approach to engaging with audience data work at the V&A

The last presentation was given by Dr Marie Hobson (Senior Manager, Audience Research and Insight, V&A) who centred her talk on how she applied organisational learning theory to her place of work. She started by defining a learning organisation as one that (1) has capacity to learn effectively and prosper, (2) detects and addresses problems, and (3) adopts a questioning attitude to assess whether policies, practices and products meet its needs within its realm. Marie noted that museums are learning organisations, albeit of the kind in which change tends not only to happen slowly, but often in response to a crisis. This was evident during the COVID-19 pandemic following the unexpected closure of physical museum sites. Museums were compelled to pivot and prioritise expanding their digital offer — often for the first time.

It is fair to say that the considerable scale and fast pace at which museums created their digital offer is unlikely to have been achieved without the urgency caused by lockdowns. But even before the pandemic, museums had been increasingly operating in an uncertain and complex environment — one in which changes were happening more quickly and on wider scales than in the past.

The post-pandemic period has only catalysed that. One crucial change has been that museums are operating increasingly like businesses, something that is requiring museums to incorporate business management strategies into their operating models. Returning to the application of organisational learning theory, Marie explained that museums — and public cultural organisations in general — reflect a paradox in the sense that they focus on the learning of their visitors (i.e., visitor needs, wants, expectations and prior knowledge) but often do not value the learning of staff and the organisation. This is problematic because it stifles endeavours to become effective learning organisations. One way to overcome the organisational learning paradox is clearly to draw on the learning of staff across organisations while broadening their audience research remit to include key, emergent data sources and functions. This reflects a trend that began in 2018 with the establishment of the Culture, Data and Research Network (CDRN) and the Visitors Studies Group (VSG) whose conference in the same year — attended mostly by learning researchers in the heritage sector — focused on the topic of Big Data.

Since then, the increase in audience data-related roles within cultural and museum organisations has been noticeable — with role holders embedded in offices within digital departments, marketing teams and communications units among others. Regardless of where role holders sit, their overarching responsibility is to harness the large amounts of data sources now available in organisations to generate insight. From an organisational learning perspective, this is being done in three main ways — according to Marie. First, looking at visitor numbers to understand what visitor targets should be and measure performance against them. Second, studying visitor demographics and understanding what audiences think of the experience — before then analysing performance to inform adjustments as and when may be needed. Third, focusing on visitor (and staff) learning to understand how barriers to learning and engagement can be removed.

Exploiting data for troubleshooting and addressing barriers to engagement in alignment with organisational learning theory

To this end, employing primary and secondary research can be beneficial. Where a lack of in-house research capacity exists, choosing not to conduct research altogether cannot be an option. At the V&A, for instance, the organisation opted against commissioning external agencies by (1) recruiting a full-time junior audience researcher to save commissioning costs, and (2) acquiring an audience analyst that had sat in a Tech team and whose role description was changed to incorporate more primary and secondary research. For example, one of the new responsibilities of the audience analyst involves testing the appeal of V&A exhibition topics to inform exhibition strategy. Marie narrated that both roles use different data and types of audience research and require different skillsets and expertise — although clear overlap exists. The audience analyst applies more data science while the audience researcher works more with qualitative research techniques. Taking an underperforming exhibition as an illustrative example of overlap (but also close collaboration) between the roles, Marie recounted the following. The audience analyst discovered that an exhibition was not receiving as many visitors as had been predicted. The exit survey data from the exhibition was very low in comparison to other recent exhibitions. Closer reading of the survey revealed that the exhibition was not attracting the organisation’s younger audiences — triggering the need for a quick response.

The audience data and research team at the V&A

The audience data and research team at the V&A

The audience researcher conducted some intercept interviews with younger audiences around the museum — asking why they had not visited this exhibition. The audience researcher found out that the reason was a low awareness of the subject matter. Interview respondents were not sure what the exhibition was about and whether or not they would enjoy it. And being amid the cost-of-living crisis, respondents indicated they were not prepared to spend money on an unknown quantity — as it were. This finding was compared to general exit survey information which showed that the ticket cost was more of a barrier to people visiting this exhibition than other recent exhibitions. The key learning point was that audiences prefer tried and tested content particularly during financially hard times. While this learning came too late to change the exhibition in question, it strongly suggested to the organisation that the appeal of a topic can be significantly shaped by the wider economic climate and that this is a vitally important factor to consider when making decisions relating not only to exhibitions, but also the overall offer of the organisation.

At a strategic level, the work of the audience analyst and audience researcher is supporting programming to effectively remove barriers to audience engagement. The research approaches both role holders have brought to programming are changing the ways of working and thinking at the V&A, thereby enabling the organisation to operate more smartly and respond quickly to wider sectoral trends and a broad economic climate. This demonstrates organisational learning theory in action.

Creating spaces for conversation, constructive critique, reflection, and learning going forward

During the Q&A session that followed, selected aspects that were discussed revolved around (1) the practical step-by-step implementation of the audience segmentation model at the NLS, (2) what building audience-related business across the Barbican is shaping up to become, (3) whether or not latest technologies such as AI are initiating new systems and novel processes that are fundamentally altering engagement with data and audiences, and (4) the accessibility and ethical considerations that need to be borne in mind when collecting and evaluating data from audiences with additional needs (e.g., people with learning difficulties or those for whom English is not a first language).

Dr Sophie Frost reflects on her take on the event presentations and discussion

Dr Sophie Frost reflects on her take on the event presentations and discussion

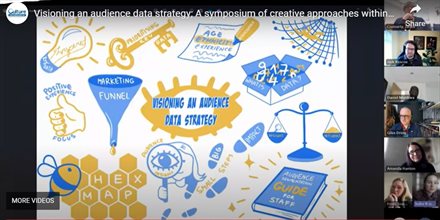

Indre Rimselyte showcases her fantastic animated artwork capturing selected points of discussion during the event

Indre Rimselyte showcases her fantastic animated artwork capturing selected points of discussion during the event

Dr Sophie Frost was invited to offer her reflections on the event. She focused on: (1) embracing a creative organisational mindset to data strategy development, (2) adopting a realistic and values-led approach underpinned by asking the right questions and the courage to talk about failure and conflict, (3) endeavouring to scope out and evaluate audience data at the start rather than at the end, (4) ensuring that people are placed at the heart of data, demonstrating a readiness to lead the discussion, and seeking to wield influence to drive decisions forward, and (5) creating spaces such as the symposium to engage in conversation and to listen to critical friends — including learning about what is happening outside of one’s organisation and across the sector. This reflection was followed by a visual live illustration created skilfully by the multidisciplinary artist — Indre Rimselyte. Her impressive artwork gathered some of the key aspects discussed by the speakers and turned them into a visual animation that helps viewers digest information easily. Amanda Hanton then concluded the symposium — impressing upon attendees that their actions matter, that those actions start with ripples, and that their impact can be very unexpected.

You can access the full recording of the event on the Culture Leicestershire website.