By Daniel H. Mutibwa, Cat Rogers, and Amanda Hanton

Introduction

Cultural provision and associated partnerships play a significant role in enriching people’s lives through inspiration, education and capacity-building (Gray, 2002; ACE, 2021; AHRC-DCMS, 2021). Local authorities have been their greatest funders. But with budgets under unprecedented pressure due to enduring austerity and numerous national and global crises (County Councils Network, 2022; HM Government, 2022; World Economic Forum, 2023), significant and successive cuts are being made — leading to considerable adverse effects (Open Access Government, 2019; Rex, 2020; Butler, 2023). One effect is the exacerbation of the already stark existing structural inequalities around access to the arts and culture across the UK (Mansfield, 2014; Harvey, 2016; Gross and Wilson, 2020; Mutibwa, 2022). This paper explores how a partnership between the University of Nottingham and Leicestershire County Council (LCC) is responding innovatively to this challenging financial and political environment — in close collaboration with cross-sectoral partners. Drawing on critical evidence and rich insights gathered via numerous consultation exercises, focus groups, interviews and insight-gathering events at local, regional and national levels, the paper discusses how LCC in particular, and local authorities in multistakeholder partnerships in general, could be best supported to navigate the constantly evolving cultural landscape in their capacities as political entities, commissioners and public service providers.

Reviewing the current cultural landscape and local authorities trapped in ‘dire’ and ‘new territory’

Cultural services play a pivotal role in enhancing the quality of people’s lives. The same can be said for the organisations and practitioners that provide those services. In addition to introducing people to the intrinsic value of the arts, culture and heritage, cultural services also deliver a wide range of outcomes. For example, cultural services (1) facilitate the development of new and adaptive skills such as critical thinking and experimentation that are transferable to a wide range of occupational contexts, (2) enable local communities to develop civic engagement competencies and local pride through involvement in the revitalisation of the places in which they live and work, (3) promote local economic growth through the creation of employment opportunities in the creative and visitor economies, (4) contribute to addressing people’s health and wellbeing through bringing together local communities at times of individual and collective crises, but also at times of celebration, and (5) remain an essential outlet through which many people learn about, and experience, the world around them (Neelands et al., 2015; Arts Council England, 2021; Local Government Association, 2022; Mutibwa, 2022). To put in context just how essential cultural services are, the United Nations designates engagement with them as a human right — one whereby ‘[e]veryone has the right freely to participate in the cultural life of the community, to enjoy the arts and to share in scientific advancement and its benefits’ (United Nations, 1948: n.p).

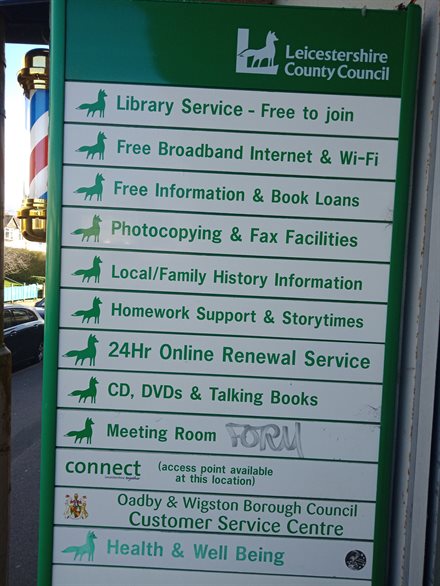

Oadby Library and a selection of its crucial cultural offer @ VCCC project

Oadby Library and a selection of its crucial cultural offer @ VCCC project

But just because the United Nations designates engagement with cultural services as a human right does not mean that those services merely exist without support. Far from it, a wide range of stakeholders provide that support in different forms and ways. Examples include (1) tiered levels of government (e.g., county and district/borough councils as well as unitary/combined/mayoral authorities), (2) arms-length bodies (e.g., Arts Council England, Historic England), foundations and trusts (e.g., Calouste Gulbenkian, Paul Hamlyn), civil society organisations and the private sector. For the purposes of this paper, the focus is placed on councils.

According to the Local Government Association (2022: n.p), councils in England in particular sit at the heart of the cultural landscape — running and supporting a nationwide network of arts, cultural and heritage organisations ranging from 3,000 libraries to 350 museums to 116 theatres to numerous castles and amusement parks to monuments and historic buildings to parks and heritage sites. It is worth noting that whilst cultural spend is a small part of the wider offer that councils provide, ‘they remain the biggest public funders of culture nationally, spending £2.4 billion a year in England alone on culture and related services’ (ibid.).

However, councils are facing considerable challenges — some of which are longstanding, and others relatively new. Nearly all of those challenges stem from a combination of national and global crises which have ranged from the Financial Crisis of 2007-2008 whose aftermath led to the launch of the austerity programme in 2010 in the UK to the exponentially mounting cost of statutory services, especially adult and social care as a result of an ageing population to persistent (illegal) immigration to BREXIT and the COVID-19 pandemic to the geo-political, military conflict in Europe — and resultant energy and cost-of-living crises as well as rising inflation (County Councils Network, 2022; HM Government, 2022; Rex and Campbell, 2022; Martin and Richardson, 2023; World Economic Forum, 2023; Gilmore, 2024).

This state of affairs has placed the budgets of authorities (local and central government alike) under unprecedented pressure. As in the past during times of perceived economic crisis, cultural spend has been affected the most (Hesmondhalgh et al., 2015; Neelands et al., 2015; Harvey, 2016; Durrer et al., 2023).

As a consequence, significant and successive cuts are being made to museums, libraries and the arts (Open Access Government, 2019; Rex, 2020; Butler, 2023). A breakdown by cultural service shows that the net spend on culture and heritage by councils has declined dramatically by 35.5 per cent between 2009/2010 and 2019/2020, and that on libraries by 43.5 per cent (Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities, 2023). A further breakdown drawing on a new analysis by the County Council Network is instructive here. Aysha Gilmore reports that council spend on ‘libraries and tourism has reduced by almost £500m since the onset of austerity’ and that while ‘English councils budgeted to spend almost £1.6bn on library services, culture, heritage and tourism’ in 2010/2011, their ‘latest accounts show that £1.1bn was spent on these services in 2023/24, a £470m decrease from 14 years ago’ (Gilmore, 2024: n.p). Gilmore notes further that library services have experienced the greatest cuts — totalling £232.5m since 2010 (ibid.) The situation is further compounded by the fact that councils are being asked to make even more substantial savings in the coming years. Proponents of budget decreases for cultural services argue that investing in museums, libraries and theatres at such a time of major confluence of crises would seem misguided. Opponents counter — recounting that places and regions without support for cultural services would risk losing out further as traditional sites of culture, heritage and community, thereby exacerbating the already stark existing structural inequalities across the UK (Mansfield, 2014; Harvey, 2016; Gross and Wilson, 2020; Mutibwa, 2022; Rex and Campbell, 2022).

Demonstration against Suffolk County Council’s proposed cuts to arts and cultural funding in January 2024 @ Charlotte Bond / Ipswich Star

Demonstration against Suffolk County Council’s proposed cuts to arts and cultural funding in January 2024 @ Charlotte Bond / Ipswich Star

Of the numerous factors that have put enormous pressure on council budgets — and by extension fostered considerable reduction in spending on cultural services even before the COVID-19 pandemic struck, the rising demand for statutory services (particularly adult and social care as well as special educational needs for young people) has often been cited as the most extremely pressing (Davies et al., 2023; Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities, 2023; Martin and Richardson, 2023). Perhaps unsurprisingly, the pandemic has exacerbated the already considerable pressures — as have the cost-of-living and inflation crises (County Councils Network, 2022; World Economic Forum, 2023). With the exception of the accommodation and food sectors, no sector has been severely affected by the pandemic than the arts, cultural and heritage sectors (Tobin, 2020; Sargent, 2022; Walmsley et al., 2022). And whilst the UK Government acted decisively in establishing the Culture Recovery Fund (AHRC-DCMS, 2021; UK Parliament, 2021a) and providing councils with a wide range of support packages (Brien, 2023; Local Government Association, n.d) to plug gaps and stimulate recovery, the cost-of-living crisis and rising inflation are unhelpfully undermining these efforts. The chairman of the Local Government Association — Councillor James Jamieson (2022: n.p) — captures the gravity of the situation aptly when he notes that ‘the dramatic increase in inflation has undermined councils’ budgets. Alongside increases to the National Living Wage and higher energy costs, this has added at least £2.4 billion in extra costs onto the budgets councils set in March [2022]’.

Jamieson notes further that ‘having faced a £15 billion real terms reduction to core government funding between 2010 and 2020’, councils are not only grappling with future financial sustainability and local services that are already on a cliff-edge, but also ‘facing a funding gap of £3.4 billion in 2023/24 and £4.5 billion in 2024/25’ (2022: n.p). It is no wonder that council after council in England is going bankrupt (Butler, 2023; Harris, 2024). The situation is predicted to get only worse if ‘an extra £350m as a short-term measure to ease the pressure’ is not immediately provided by central government (Martin and Richardson, 2023: n.p). Councillor Nick Rushton — the leader of Leicestershire County Council — has remarked that even councils that are ‘super-efficient, decisive and not ducking difficult decisions’ find themselves in a ‘dire’ situation whereby ‘spiralling costs are making it much harder to keep [their] head[s] above water’ and, as such, are ‘reaching new [uncharted] territory’ (cited in Martin and Richardson, 2023: n.p). If past funding cuts during times of economic crises (imagined or real) are anything to go by, this does not bode well for the arts, cultural and heritage sectors. With councils clearly having their backs against the wall, this begs the question: where do they go from here? And what does this unprecedented circumstance mean for the support of cultural services? What does it mean for local communities and others with a stake in those services? Might the formation of partnerships be part of the answer? If so, what might such partnerships look like in future, especially those that are inclusive, meaningful, purposeful and sustainable?

Looking Back to Look Forward

The practice of looking back to look forward affords us an opportunity to gain a better understanding of connections between the past and present as we envision the future (Knight, 2016: v).

It is fair to say that even in circumstances where councils did not face such major financial challenges as described above, they would benefit from collaborating closely with numerous stakeholders within and outside the cultural ecosystems they support. Cases in point include cultural organisations and venues, artists and creative businesses, faith groups, youth services, actors in the Voluntary, Community and Social Enterprise (VCSE) sector, the private sector, colleges and universities. Whilst these stakeholders would not have the capacity to help plug the massive financial gaps that councils are facing, building partnerships with them has huge potential to provide councils with some much-needed respite — however brief. And it is here that looking at the past can add value in the search for what appropriate partnerships might look like in future. Wanda B. Knight — an arts education and cultural studies scholar — persuasively argues that ‘[f]oresight does not exist without hindsight [meaning] we can benefit from the lessons learned from looking back’ (2016: v). For our purposes in this paper, we focus on partnerships among councils, universities and local communities — but do allude to other stakeholders wherever relevant. A review of literature on past council partnerships with universities and local communities reveals good reasons for the establishment of such partnerships. They have been found to generate mutual benefits in terms of funding, efficiency and cross-fertilisation of ideas among many other things. Councils and universities have a lot in common — with one commonality reflected in working with local communities in various capacities.

Members of Leicestershire's diverse local communities at the Volunteer Sharing Day at County Hall in Glenfield in March 2023 including councillors, frontline officers, school pupils, arts, cultural, and heritage champions, and university researchers

Members of Leicestershire's diverse local communities at the Volunteer Sharing Day at County Hall in Glenfield in March 2023 including councillors, frontline officers, school pupils, arts, cultural, and heritage champions, and university researchers

We find it helpful here to make use of the seminal work by Ian Hutchcroft who worked as an Environment Officer for Devon County Council whilst pursuing doctoral research at the University of Plymouth back in the mid-1990s when writing about alliances on and around sustainable development between local authorities, universities and local communities. Ian Hutchcroft noted that ‘[i]n any community, certainly those with a major urban area, the university will be one of the largest employers, spenders and influencers in the area’ (1996: 219).

The same can be said for councils as political entities, commissioners and public service providers. Councils employ millions of people, are responsible for hundreds of functions that significantly shape places and regions, and — as explained by Councillor James Jamieson above — also spend billions per annum totalling up to at least one quarter of public expenditure (Brien, 2023).

In these capacities, both councils and universities have a responsibility ‘to engage actively [with] the communities which they serve and are a part of’ (Hutchcroft, 1996: 219). At the time Ian Hutchcroft wrote his article, he lamented what he viewed as a siloed approach taken by councils and universities which did not serve local communities effectively and meaningfully. Hutchcroft championed institutional change — arguing that adopting local authority/university partnerships would facilitate ‘mutual support, cross-fertilisation of ideas, identification of common objectives, [and] joint working [thereby] resulting in [local authorities and universities] becoming part of a dynamic, wider community rather than separate parts of a compartmentalised community’ (1996: 220). What Hutchcroft argued for in 1996 in relation to sustainable development would become reality in the context of cultural partnerships over a decade later.

Until the mid-2000s in the UK, engagement with external bodies such as councils and local communities — a process which later came to be known as public engagement — was not quite part of what universities understood their core mission to be. The research-driven culture at UK universities at the time did not align with the demands and vision of public engagement (Mawson, 2007). In addition, public engagement was not well regarded by university researchers who felt that it was hard to resource because it did not bring in significant funding (Duncan and Manners, 2012: 222). From 2008 onwards, however, this gradually began to change with the establishment of initiatives such as the Beacons for Public Engagement (Duncan and Manners, 2012) and, in 2010, the launch of the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) Connected Communities Programme (Facer and Enright, 2016). Both initiatives championed ‘outward-facing, dynamic, and two-way exchange with the world outside the academy [supported] by a host of external policy drivers [based on the understanding] that universities are there to “make a difference” and to transform individuals’ lives’ (Duncan and Manners, 2012: 221). Ever since the early 2010s, those ‘external policy drivers’ have used universities as a commercial, cultural, knowledge and technology driver for the government’s regional development agenda designed to raise national and regional productivity levels (Mawson, 2007; AHRC-DCMS, 2021; Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities, 2023; Corner, 2024). A case in point is the UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) Challenge Fund — also referred to in some discourses as the Industrial Strategy Challenge Fund (UK Government, 2017). Unsurprisingly, there have been critical voices that have pointed to the constraining nature of this arrangement — arguing that the government needs to ensure that the financial support awarded to universities allows for more flexibility, freedom and autonomy than is currently the case (Mawson, 2007; UK Parliament, 2021b).

The Creative Communities programme emphasises the value of collaborative partnerships

The Creative Communities programme emphasises the value of collaborative partnerships

Out of these past developments has emerged a body of knowledge underpinned by principles and practices on and around public engagement that can usefully inform how inclusive, meaningful, purposeful and sustainable cultural partnerships among local authorities, universities and local communities might look like in future.

For instance, public engagement is now formalised and embedded as a valued and recognised activity for many university researchers through iterations of the frameworks for knowledge exchange, research excellence and societal impact broadly considered (National Co-ordinating Centre for Public Engagement, n.d; Research Excellence Framework, 2024; UK Research and Innovation, 2024). More than ever before, local authorities that have partnered with universities and local communities on projects of shared affinities and interest understand the value of (1) working flexibly in partnership with various stakeholders, (2) inviting the broadest possible perspectives from outside council circles, and (3) embracing co-production approaches to the development of solutions that sustainably address major challenges as opposed to imposing decisions designed in isolation and from a position of power (Hutchcroft, 1996; Duncan and Manners, 2012; Local Government Association, 2019; Rex and Campbell, 2022).

The Arts and Humanities Research Council-funded Creative Communities programme hosted by Northumbria University is one of several recent initiatives established to further develop the agenda outlined above.

Among many essential features, past successful cultural partnerships involving local authorities, universities and local communities are those that have (1) broken down barriers among stakeholders by demystifying partnership working, (2) involved local communities as contributors and researchers through creating opportunities for people to co-design and inform the research questions being tackled, and (3) worked collaboratively to inform policy (Facer and Enright, 2016; Gross and Wilson, 2020; Arts Council England, 2021; Mutibwa, 2022).

During an event hosted by the National Centre for Academic and Cultural Exchange (NCACE) held in October 2023 on the topic of ‘University and Local Authority Cultural Partnerships’, Ruby Sant — a visual and multimedia artist, Director of a Community Interest Company called ‘Little Lost Robot’, and Creative and Cultural Development Officer at Bath Spa University who works in close liaison with the West of England Combined Authority — added two further facets that helpfully tie the features above together. She used the terms a ‘triumvirate of connections’ and ‘network of equity’ to describe the richness of links and the importance of working in equal partnership for wider benefit as central qualities underpinning the meaningfulness and success of multistakeholder cultural partnerships (Sant, 2023). In what follows — and based on some of the past learning discussed above, we explore how a university-local authority policy impact project on and around the arts, culture and heritage between the University of Nottingham and Leicestershire County Council (LCC) is supporting the latter to navigate as effectively as possible the challenging cultural landscape discussed earlier. It is our hope that some of the learning here would be of interest to other university/local authority cultural partnerships involving multiple stakeholders.

Visioning a Creative and Cultural County: Developing Leicestershire County Council’s Cultural Strategy (VCCC)

Visioning a Creative and Cultural County (VCCC) is developing a Cultural Strategy as an LCC policy document through joining up culture, heritage, and the creative industries in a way that delivers inclusive and sustainable cultural, economic, health and social outcomes for the people of Leicestershire. This work is happening against the backdrop of austerity, a challenging financial and political climate, and recent award of Arts Council England’s National Portfolio Organisation funding. Research-policy impact work on VCCC is being undertaken with the ultimate goal of contributing to (1) unlocking and spreading opportunities for cultural engagement more equitably amongst diverse local communities across Leicestershire, (2) revitalising the cultural and social fabric(s) of the county, and (3) stimulating creativity to improve productivity and to contribute to an inclusive economy. The backstory to VCCC has its origins in the developments in the cultural landscape that we have discussed in this paper thus far. Two strategic leaders at Leicestershire County Council (LCC) — Cat Rogers and Franne Wills — mooted the idea of creating a Cultural Strategy already in the early 2010s. This was in the immediate aftermath of the launch of the austerity programme mentioned earlier. The creation of a Cultural Strategy was prompted by the withdrawal of creative and cultural service provision that was felt by LCC officers and end users to be extremely beneficial. The thinking at the time was that a Cultural Strategy would highlight the value and benefit of service provision, something that would be very helpful to present as a reference point to decision-makers — primarily Heads of Service within LCC and councillors. Tying this to the LCC Strategic Plan at the time was seen to be extremely essential.

Cat Rogers speaking at an event for creatives © Creative Leicestershire

Cat Rogers speaking at an event for creatives © Creative Leicestershire

As a result of the major challenges discussed above, it would take around a dozen years until the foundation for the development of an LCC Cultural Strategy was laid in late 2022 and early 2023. Learning from past university/local authority cultural partnerships shows that contacts and working relationships developed from existing collaborations can be built upon to initiate further, deeper links and work on and around shared agendas, affinities and interests. This is exactly how VCCC was formed.

LCC colleagues expressed a clearly identified need, university researchers shared that agenda and committed to working closely with LCC colleagues to address the specified need. With the benefit of hindsight, it is fair to say that LCC colleagues clearly championed institutional change — the kind that Ian Hutchcroft (1996) argued for back in the day. They could have sat back and done nothing — in the hope that things might change for the better. But they did not. They sought to do something.

In doing so, they demonstrated that they are progressive in orientation and that they want to make a difference to the quality of life of the diverse local communities across Leicestershire that they serve. This demonstration of commitment in the midst of very challenging circumstances that local authorities have been compelled to work under is remarkable. The university researchers on VCCC have also shown a commitment to (1) working side by side with LCC colleagues and with as many members as possible of the diverse local communities that LCC serves, (2) bringing an openness and willingness to learn about the inner workings of local government — including the analytical and operational needs of LCC colleagues, and (3) understanding LCC’s stakeholders — both within and outside Leicestershire’s creative and cultural ecosystem.

Partnership working on VCCC has been strongly guided by the co-production ethos which has informed the collective process of (1) identifying LCC’s policy needs in relation to joining up cultural provision, heritage service delivery, and the creative industries under a Cultural Strategy, (2) evaluating the feasibility of undertaking associated preparatory work, (3) developing a programme of research activities, consultation exercises and knowledge exchange events to support the overarching objective, (4) determining the overall project budget and related spend, (5) articulating how the process of Cultural Strategy development will inform policy development and related impact, and (6) reflecting on how policy impact work will be taken forward beyond March 2024 when the project ends. Ever since austerity struck, LCC budgets have been much tighter, and workload pressures much higher. This has reduced the capacity to conduct research in-house. The research capacity that university researchers have brought to VCCC would clearly not have been available to LCC under those circumstances. By the same token, university researchers would not have been able to conduct research in preparation for the development of a Cultural Strategy for LCC outside the context of VCCC — had LCC colleagues not articulated its need, especially at such a time when spend on the arts, culture and heritage appears to be continually under threat. Twenty-eight years ago, Ian Hutchcroft dreamt of researchers and local authorities ‘having a foot in each other’s camps’ (1996: 223) as they strove to serve the local communities they are a part of. VCCC is a clear embodiment of that today — as are many other university/local authority cultural partnerships doing similar impactful work.

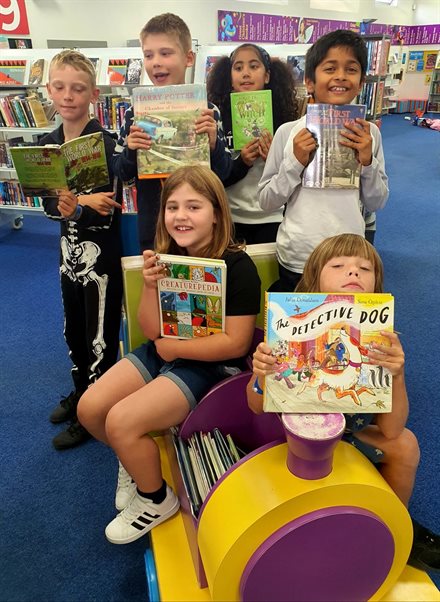

Children at LCC's libraries' Festival of Stories © LCC

Children at LCC's libraries' Festival of Stories © LCC

To date, VCCC has been driven by invaluable input from (1) strategic leaders and frontline officers from different teams and units within LCC, (2) creative practitioners across the county, (3) members from diverse local communities, and (4) officers from district and county councils in Fenland, Derbyshire and Kent. Input has informed the production of a blueprint to inform the next steps of developing a Cultural Strategy for LCC. Like many past university/local authority cultural partnerships, VCCC has prided itself on being inclusive and purposeful — a feature that many stakeholders have related with.

Among other things, this has contributed to the generation of very interesting and insightful findings that are going to serve the process of Cultural Strategy development very well going forward. For instance, despite minor reservations about whether or not LCC needs a Cultural Strategy — there was a general consensus amongst stakeholders that a Cultural Strategy could help demonstrate, in a tangible way, the value that LCC assets have for local communities.

Examples of assets include libraries, museums, parks, monuments, historic buildings and heritage sites. Capturing that value effectively could help justify the importance of those assets and the impact of associated cultural engagement. Over and beyond capturing value and impact, a Cultural Strategy could be used to (1) link cultural provision to LCC's broader strategic agendas and priorities as outlined in the Strategic Plan (2022-2026) (Leicestershire County Council, 2022), (2) apply for grants to develop and fund more cultural activities underpinned by co-creation between LCC and the diverse local communities it serves — with possible involvement of university researchers if desired, and (3) aid LCC officers in decision-making — with a sense of clarity of purpose, including a certain level of protection.

For LCC going forward, it is clear — based on the key insights gathered so far — that developing a Cultural Strategy would be a valuable investment in terms of (1) articulating cultural offerings much more clearly and strongly, (2) enhancing cultural engagement in ways that (a) render those offerings much more visible to the public, and (b) enable more people to engage with the offerings to enrich their lives, (3) building new collaborative partnerships both within and outside the county council, (4) engaging more effectively and regularly with local communities — both existing and new, (5) empowering frontline officers as cultural advocates and ambassadors, and (6) supporting creative practice and creative practitioners in ways that enable them to (a) build capacity, (b) connect to networks of other creative people and organisations across the county, and (c) grow their creative entrepreneurial capabilities. In addition, VCCC has found that it is going to be vital to put in place a steering group to ensure that the role and value of an LCC Cultural Strategy are understood both within and outside the county council. In times of economic crisis such as these, all this adds great value and much-needed visibility to LCC’s cultural services and the officers that look after them. To succeed in this endeavour, working in close partnership with stakeholders in the cultural ecosystem within Leicestershire is going to be critical because it is these stakeholders that are going to benefit the most from the opportunities and possibilities offered by a Cultural Strategy.

A collage of images taken at the VCCC project conference (July 2023)

A collage of images taken at the VCCC project conference (July 2023)

As in past effective university/local authority partnerships, these stakeholders could range from cultural organisations and venues to artists and creative businesses to faith groups and youth services to local charities and voluntary sector to sports and other relevant interest groups to universities and colleges. In addition to these stakeholders — and in the absence of a cultural compact (Arts Council England, 2020) in Leicestershire at the time of writing, LCC could take the initiative by bringing together stakeholders outside the county’s cultural ecosystem.

Such stakeholders could include representatives from tiered council levels, businesses, and education providers among others that could be brought on board with a view to (1) consulting on and co-designing a vision for the role of culture in Leicestershire, and (2) delivering against shared priorities.

Conclusion

As a university/local authority/local community cultural partnership, VCCC is responding to the needs and possibilities of the arts, cultural and heritage ecosystem in Leicestershire during challenging and turbulent times. Rather than reinventing the wheel, VCCC is providing responses by drawing on constructive learning generated from past cultural partnerships. VCCC has demonstrated commitment to co-producing knowledge and research insights with university researchers, LCC officers, creative practitioners and diverse local communities at all stages of partnership working. In doing so, VCCC has drawn on theories and methods of academic research, local government expertise and technical knowhow, and experiential knowledge generated by creative practitioners and community members across Leicestershire. By bringing together multiple stakeholders to generate these different types of knowledges in an effort to inform the process of developing a Cultural Strategy for LCC — and ultimately enacting the Strategy into policy in future, VCCC has shown the powerfulness and value of cultural partnerships involving universities, local government, local communities and variously situated actors within Leicestershire’s cultural ecosystem. In reflecting on the foundational work of Cultural Strategy development that VCCC has achieved thus far, we find it helpful to point to the motivations that have driven stakeholders to contribute so generously to this essential venture. Here, we draw on the typology that Keri Facer and Bryony Enright very helpfully developed when characterising the kinds of people that were drawn to community/university partnerships in the context of the AHRC Connected Communities Programme mentioned earlier. Like those people, VCCC stakeholders are:

generalists and learners (who are interested in new ideas and connections), makers (who are interested in getting something tangible made or changed), scholars (who are interested in finding opportunities to pursue specific interests), entrepreneurs (who are attracted by the funding opportunities), accidental wanderers (who end up in the programme by happenstance), advocates for a new knowledge landscape (who are explicitly looking to experiment with new ways to create knowledge). These motivations are characteristic of both university and community partners. 98% of survey respondents reported they would do this sort of collaborative work again (Facer and Enright, 2016: 2).

Like the ‘university and community partners’ alluded to above, virtually all VCCC stakeholders have (1) demonstrated great enthusiasm for the possibilities that lie ahead, (2) valued the genuinely empowering co-production approach taken on the VCCC project, and (3) expressed strong interest in remaining involved in Cultural Strategy development work going forward. A key reason for this is two-fold: (1) stakeholders can very clearly see where their contributions and involvement are making a difference, and (2) they can also very clearly vision what VCCC as a multistakeholder cultural partnership can do for them — both in tangible and intangible ways. This is what inclusive, meaningful, purposeful and sustainable university/local authority/local communities should look like in future in the areas of the arts, culture and heritage. Such partnerships should co-design an inclusive and shared vision of creative and cultural engagement with diverse stakeholders in places and regions. The partnerships should support local authorities to transition from being merely political entities and service deliverers to becoming genuine partners working collaboratively and in equal partnership to achieve the greatest impact possible for places and regions through offering tailored and meaningful cultural services. Those partnerships should co-lead on futureproofing the design and co-delivery of cultural services in ways that consider the evolving circumstances and demographics in places and regions in future.

Note

A shorter version of this post was published as an essay for the National Centre for Academic and Cultural Exchange (NCACE). The essay appeared in the NCACE Collection Series titled Universities, Local Authorities, and Culture-based Partnerships: Case Studies, Reflections, and Evidence from REF Impact Case Studies.

References

-

AHRC-DCMS (2021). Boundless Creativity: Culture in a Time of COVID-19. London: Crown Copyright. Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/boundless-creativity-report (Accessed 17 November 2021).

-

Arts Council England (2020). Review of the Cultural Compacts Initiative. Available online at: https://www.artscouncil.org.uk/sites/default/files/download-file/201102_Compacts_Report%20_031220_0.pdf (Accessed 06 May 2022).

-

Arts Council England (2021). Let’s Create: Strategy 2020–2030. London: ACE. Available online at: https://www.artscouncil.org.uk/our-strategy-2020-2030 (Accessed 23 October 2021).

-

Brien, P. (2023). Local Government Finances. House of Commons Library. Available online at: https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-8431/ (Accessed 19 January 2024).

-

Butler, P. (2023). Majority of English Councils Plan More Cuts at Same Time as Maximum Tax Rises. The Guardian. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2023/mar/07/english-councils-cuts-services-maximum-tax-rises-local-finances (Accessed 13 March 2023).

-

Corner, J. (2024). Spinning Out the Benefits of Academic Research. UK Research and Innovation. Available online at: https://www.ukri.org/blog/voices-spinning-out-the-benefits-of-academic-research/?utm_medium=email&utm_source=govdelivery (Accessed 08 February 2024).

-

County Councils Network (2022). County Spotlight: Cost of Living Crisis: Supporting Those Most in Need in County Areas. London: CCN.

-

Davies, N., Hoddinott, S., Fright, M., Nye, P., Shepley, P., and Richards, G. (2023). Performance Tracker 2022/23 Spring Update. Institute for Government. Available online at: https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/sites/default/files/2023-02/Performance%20Tracker%202022-23%20Spring%20Update.pdf (Accessed 14 January 2024).

-

Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (2023). Local Authority Revenue Expenditure and Financing England: 2021 to 2022 Individual Local Authority Data — Outturn. Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/local-authority-revenue-expenditure-and-financing-england-2021-to-2022-individual-local-authority-data-outturn (07 November 2023).

-

Duncan, S., and Manners, P. (2012). ‘Embedding Public Engagement within Higher Education: Lessons from the Beacons for Public Engagement in the United Kingdom’. In: L. McIlrath, A. Lyons, R. Munck (eds.). Higher Education and Civic Engagement. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 221–240.

-

Durrer, V., Gilmore, A., Jancovich, L., and Stevenson, D. (2023). Cultural Policy is Local: Understanding Cultural Policy as Situated Practice. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

-

Facer, K., and Enright, B. (2016). Creating Living Knowledge: The Connected Communities Programme, Community-University Partnerships and the Participatory Turn in the Production of Knowledge. Arts and Humanities Research Council. https://connectedcommunities.org/index.php/creating-living-knowledge-report/ (Accessed 03 May 2016).

-

Gilmore, A. (2024). CCN: Council Spending on Libraries and Culture Reduces by Nearly £500m. 151 News. Available online at: https://www.room151.co.uk/151-news/ccn-council-spending-on-libraries-and-culture-reduces-by-nearly-500m/ (Accessed 05 February 2024).

-

Gray, C. (2002). Local Government and the Arts. Local Government Studies, 28(1), 77–90.

-

Gross, J., and Wilson, N. (2020). Cultural Democracy: An Ecological and Capabilities Approach. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 26(3), 328–343.

-

Harvey, A. (2016). Funding Arts and Culture in a Time of Austerity. London: New Local Government Network.

-

Harris, J. (2024). One by One, England’s Councils are Going Bankrupt – and Nobody in Westminster Wants to Talk about It. The Guardian. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2024/jan/14/englands-councils-bankrupt-westminster (Accessed 11 February 2024).

-

Hesmondhalgh, D., Oakley, K., Lee, D., and Nisbett, M. (2015). Culture, Economy, and Politics: The Case of New Labour. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

-

HM Government (2022). Levelling Up the United Kingdom. London: Crown Copyright. Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/levelling-up-the-united-kingdom (Accessed 04 September 2022).

-

Hutchcroft, I. (1996). Local Authorities, Universities and Communities: Alliances for Sustainability. Local Environment, 1(2): 219–224.

-

Jamieson, J (2022). Council Cost Pressures — A Comment Piece by Cllr James Jamieson. Local Government Association. Available online at: https://www.local.gov.uk/about/news/council-cost-pressures-comment-piece-cllr-james-jamieson (Accessed 07 October 2023).

-

Knight, W. B. (2016). Looking Back, Looking Forward Editorial. Visual Arts Research, 42(2): v-viii.

-

Leicestershire County Council (2022). The Strategic Plan. Glenfield: Leicestershire. Available online at: https://www.leicestershire.gov.uk/about-the-council/council-plans/the-strategic-plan (Accessed 14 December 2022).

-

Local Government Association (2019). New Conversations 2.0: LGA Guide to Engagement. London: LGA.

-

Local Government Association (2022). Cornerstones of Culture. London: LGA. Available online at: https://www.local.gov.uk/topics/culture-tourism-leisure-and-sport/cornerstones-culture (Accessed 04 February 2023).

-

Local Government Association (n.d). COVID-19: Council Finances. London: LGA. Available online at: https://www.local.gov.uk/our-support/coronavirus-information-councils/covid-19-service-information/covid-19-council-finances (Accessed 09 January 2024).

-

Mansfield, C. (2014). On with the Show: Supporting Local Arts and Culture. London: New Local Government Network.

-

Martin, D., and Richardson, H. (2023). Leicestershire County Council Warns of ‘Dire’ 100m Funding Gap. BBC News. Available online at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-leicestershire-66891440 (Accessed 11 February 2024).

-

Mawson, J. (2007) Research Councils, Universities and Local Government: Building Bridges. Public Money and Management, 27(4): 265–272.

-

Mutibwa, D. H. (2022). The (Un)Changing Political Economy of Arts, Cultural and Community Engagement, the Creative Economy and Place-Based Development during Austere Times. Special Issue: ‘Culture, Heritage and Territorial Identities’. Societies, 12(5) 135: 1–24.

-

National Co-ordinating Centre for Public Engagement (n.d). The Beacons for Public Engagement. Bristol: Watershed Media Centre.

-

Neelands, J., Belfiore, E., Firth, C., Hart, N., Perrin, L., Brock, S., Holdaway, D., and Woddise, J. (2015) Enriching Britain: Culture, Creativity and Growth. The 2015 Report by the Warwick Commission on the Future of Cultural Value. Warwick: University of Warwick.

-

Open Access Government (2019). £400 Million Funding Cut to Libraries, Museums, and Arts. Available online at: https://www.openaccessgovernment.org/400-million-cut-to-libraries/57706/ (Accessed 13 August 2020).

-

Research Excellence Framework (2024). Securing a World-class, Dynamic and Responsive Research Base across the Full Academic Spectrum within UK Higher Education. Available online at: https://www.ref.ac.uk/ (Accessed 19 January 2024).

-

Rex, B. (2020). Which Museums to Fund? Examining Local Government Decision-making in Austerity. Local Government Studies, 46(2), 186–205.

-

Rex, B., and Campbell, P. (2022). The Impact of Austerity Measures on Local Government Funding for Culture in England. Cultural Trends, 31 (1): 23–46.

-

Sant, R. (2023). Creative Twerton. NCACE Evidence Café 11: University & Local Authority Cultural Partnerships — 12 October 2023 [Podcast]. Available online at: https://soundcloud.com/user-245837210 (Accessed 02 November 2023).

-

Sargent, A. (2022). Covid-19 and the Global Cultural and Creative Sector: Two Years of Constant Learning — New Foundations for a New World. Leeds: Centre for Cultural Value.

-

Tobin, J. (2020). Covid-19: Impact on the UK Cultural Sector. House of Lords Library. Available online at: https://lordslibrary.parliament.uk/covid-19-impact-on-the-uk-cultural-sector/ (17 May 2021).

-

UK Government (2017). UKRI Challenge Fund: For Research and Innovation. Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/industrial-strategy-challenge-fund-joint-research-and-innovation (Accessed 03 August 2017).

-

UK Parliament (2021a). COVID-19: Culture Recovery Fund. Available online at https://committees.parliament.uk/work/1136/covid19-culture-recovery-fund/ (Accessed 23 November 2021).

-

UK Parliament (2021b). A New UK Research Funding Agency. Available online at: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm5801/cmselect/cmsctech/778/77807.htm (Accessed 03 February 2024).

-

UK Research and Innovation (2024). Knowledge Exchange Framework. Available online at: https://www.ukri.org/what-we-do/supporting-collaboration/supporting-collaboration-research-england/knowledge-exchange-framework/ (Accessed 19 January 2024).

-

United Nations (1948). Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Available online at: https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights (Accessed 27 October 2023).

-

Walmsley, B., Gilmore, A., O’Brien, D., and Torreggiani, A. (2022). Culture in Crisis: Impacts of Covid-19 on the UK Cultural Sector and Where We Go from Here. Leeds: Centre for Cultural Value.

-

World Economic Forum (2023). The Global Risks Report 2023. Cologny/Geneva: World Economic Forum. Available online at: https://www.weforum.org/publications/global-risks-report-2023/ (Accessed 22 September 2023).