The Economist

Life sentences

As the death penalty becomes less common, life imprisonment becomes more so

Reformers say life is often too long

Jul 6th 2021

BATON ROUGE AND LILONGWE

LAST AUGUST a judge sentenced Brenton Tarrant, who murdered 51 people at two mosques in Christchurch, to life in prison with no possibility of parole. It was the first time a court in New Zealand had meted out such a sentence. Jacinda Ardern, the prime minister and a liberal icon, took grim satisfaction in the punishment. “Today I hope is the last where we have any cause to hear or utter the name of the terrorist,” she said.

Lifelong imprisonment seems to be spreading as a punishment for the worst crimes. In 2019 Serbia passed “Tijana’s law” in response to the rape and murder of a 15-year-old girl. It allows judges to sentence some murderers and rapists of children to life in prison without parole. In June last year, after the gang rape of a 13-year-old girl by soldiers, Colombia overturned its constitutional ban on life sentences. Britain’s government recently proposed legislation to reduce the age at which judges can impose “whole-life” sentences from 21 to 18.

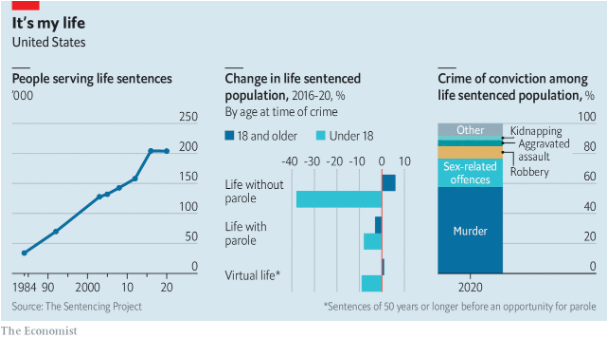

The most heinous crimes are rare, but the world’s population of lifers is large and probably growing. According to the World Prison List the population of inmates rose by 20%, to 10.4m, from 2000 to 2015. Meanwhile between 2000 and 2014 the number of people serving life sentences worldwide rose by 84%, to 479,000, according to “Life Imprisonment”, a recent book. America held 40% of them, and more than 80% of those have no prospect of parole. The Sentencing Project, a think-tank in Washington, DC, reckons that the number of Americans serving life sentences without parole rose by two-thirds, to 56,000, between 2003 and 2020. Turkey, India and Britain also lock up a lot of people for life. South African jails hold nearly 17,000 lifers, up from 500 in 1995. In 2014 some sort of formal life sentence was on the books of 183 countries and territories.

Many penal reformers think that is excessively harsh. Lifelong confinement is a declaration by the state that a person is beyond reform. It punishes long after most violent offenders have lost the will or capacity to repeat their offences. And in some countries, such sentences are imposed not only for murder and rape but also for lesser crimes.

Catherine Appleton, one of the authors of “Life Imprisonment”, contrasts the punishment of Mr Tarrant with Norway’s treatment of Anders Breivik, another fanatic, who in 2011 murdered 77 people, most at a summer camp for the Labour Party’s youth wing. He drew Norway’s maximum prison sentence of 21 years. After that, a court will decide if he is still dangerous. If so, which seems likely, he will remain locked up. But if not, he will be freed.

Opponents of life without parole hope to repeat the success of campaigners against capital punishment. Since 1976 more than 70 countries have abolished the death penalty. The number of executions worldwide in 2020 fell for the fifth year running to its lowest in a decade, says Amnesty International, a human-rights group. In America just 17 people were executed last year. If campaigners have their way, life sentences will be the next sort to be branded cruel and rendered unusual.

Making this case is not simple. For one thing, life-sentencing regimes vary enormously. Some are relatively lenient, as in Finland, where few “lifers” spend more than 15 years in prison. Others are staggeringly harsh. Some American states still lock up juvenile offenders for life. China imposes the sentence on corrupt officials. Australia and Britain do so for drug offences. Life with a chance of parole may not be much better than without it if parole is granted rarely. Life sentences can be disguised as indeterminate or very long fixed-term sentences. El Salvador, which does not impose life sentences, can lock people up for 60 years.

A bigger problem for reformers is that many have argued that life without parole is a merciful alternative to the death penalty. Michael Radelet, a sociologist at of the University of Colorado Boulder who is a prominent opponent of capital punishment, says that he is “no fan of life without parole, but the alternative to killing people is not killing them, so it’s a step in the right direction.” Many jurisdictions have taken it. Colorado replaced the death penalty last year with mandatory life sentences without parole. In 2018 Benin commuted the sentences of its last death-row prisoners to life. After the fall of communism many eastern European countries replaced capital punishment with life sentences.

Life after death

In places that retain the death penalty, the possibility of life in prison can reduce its use. In Texas death sentences “declined precipitously” after 2005, when judges first had the option of imposing life without parole instead, notes Ashley Nellis of the Sentencing Project. Thousands of death-row inmates in countries that have stopped executing people, such as Kenya and Sri Lanka, are in effect serving life sentences. “Life Imprisonment” does not count them as lifers.

Another complication is that efforts to reduce incarceration can hurt the anti-life-sentence cause. In America, where such efforts have bipartisan support, reforms to shorten sentences for non-violent crimes have the unintended consequence of making long sentences for violent ones seem more reasonable, says the Sentencing Project. Also, a recent rise in violent crime could make voters less keen on leniency.

Opponents of life sentences take issue not only with retribution-minded conservatives but also with liberals who cheer when rapists and racist killers are locked away forever. In South Africa pressure from women’s groups led to a sharp increase from 1995 to 2006 in the use of life sentences for rapists. Those who would free the likes of Mr Tarrant after a couple of decades are in effect urging their fellow citizens to show as much empathy to the criminal as to the victim. That is a big ask.

But not, perhaps a hopeless one. In Louisiana, among the most punitive states in the most punitive rich democracy, attitudes are changing. Last year the state’s jails held nearly 6,000 prisoners serving sentences of 50 years or longer, a fifth of the total prison population. Nearly 4,400 were serving life without parole, which is mandatory for five offences, including “aggravated” rape and second-degree murder, which might mean driving a getaway car. Louisiana’s version of the “three-strikes” laws introduced during a nationwide crackdown on crime during the 1990s lets prosecutors seek life in prison for repeat offenders, just one of whose four crimes needs to have been violent. One man was put away for life for attempting to steal a pair of hedge clippers.

Nearly half of Louisiana’s lifers are first offenders, according to Kerry Myers of Parole Project, an NGO in Baton Rouge, the state’s capital, that helps ex-cons adjust to freedom. Three-quarters are black. In 2016 around 300 were in prison for crimes they committed when they were children.

Until May 12th Chuck Clemons was one. Jailed for what he describes as a “senseless” murder he committed when he was 17, he served 44 years in Angola, a maximum-security lock-up larger than Manhattan that houses 6,300 inmates, nearly three-quarters of them lifers. Tall and soft-spoken, with a scholarly mien accentuated by gold-rimmed spectacles, he was not crushed by his ordeal. “What kept me going”, he says, was baking. He arose at 11:30pm on work days to confect bread rolls and such treats as banana pudding and pecan pie for 800-900 prisoners at a time.

But there were sorrows. He watched from afar as his sister married and bore children. He could not bear his nephew to visit him. “Just watching [members of my family] leave and knowing that I got to go back there, I wasn’t strong enough to take that,” he says. His mother, with whom he is now reunited, has Alzheimer’s. His father died of covid-19.

Mr Clemons’s release is a sign that things in Louisiana, and America, may be changing. In a string of decisions since 2010, America’s Supreme Court has ruled that mandatory life sentences without parole for juveniles are unconstitutional, forcing states to reconsider whether people locked up for crimes they committed as children needed to remain so. Louisiana has released 78 juvenile lifers, starting in 2016 with Andrew Hundley, now Parole Project’s director, who was jailed for killing a girl when he was 15.

Louisiana has other reasons to free prisoners who appear to pose no threat. Its incarceration rate of 980 per 100,000 people in 2018 was the highest in the country. Spending on the penal system, some $700m a year, is one of the biggest items in the budget. In 2017 with bipartisan support the state enacted a package of laws to reduce its prison population. The number of prisoners has dropped by about a quarter since 2017.

Despite such advances, life without parole is still entrenched in Louisiana’s law, says Mr Myers. Prosecutors like draconian penalties. The threat of them makes it easier to secure convictions via plea bargains; suspects often admit to a lesser crime rather than face trial for a more serious one and the possibility of being locked up forever. Mr Myers claims that politicians do what the prosecutors want.

Prosecutors merely execute the laws, retorts Loren Lampert, of Louisiana’s District Attorneys Association. Still, he thinks mandatory life sentences for murder and aggravated rape protect potential victims. Even a few children deserve such a punishment. “Some cases are so heinous, so atrocious, so aggravated that they merit that distinction of the worst of the worst,” he says. Parole hearings can force victims to “relive the most horrible event of their entire lives every two years”.

Changing tack

Some Louisianans are trying a new approach. Two businessmen and a lawyer recently founded the Second Look Alliance, which aims to cut the prison population, starting with a campaign to end mandatory life sentences without parole for second-degree murder. Legislative lobbying has gone as far as it can, says its executive director, Preston Robinson. The next phase requires “changing the hearts and minds of the public”, especially moderate and conservative voters.

He thinks three messages will resonate with them: that Louisiana’s large population of lifers makes it an “outlier” even in the south; that money spent locking people up for decades is wasted; and that redemption is possible. In the group’s first video Billy Ebarb, a white man, recalls that in 1985 his brother was killed trying to break up a fight. The killer was Charles Manuel, a black man who had committed no other crimes. With Mr Ebarb’s support he was freed after 35 years. Mr Manuel appears on screen and places his hand on his victim’s brother’s shoulder.

Some campaigners focus on the extraordinary number of elderly prisoners in America. In 2019 federal and state prisons housed 180,000 people aged 55 and older: 13% of the total, up from 3% in 1999. Keeping old people locked up is expensive. Tina Maschi of Fordham University in New York calculates that they cost $68,000 a year, three times as much as young inmates.

And they would pose little risk if freed. Of 199 prisoners aged 51 to 85 released from jails in Maryland since 2012 just five had returned by 2020 for committing a crime or violating parole conditions. Among the general population of freed prisoners, 40% were back in the pen within three years.

Politicians and courts across America are chipping away at life sentences. Legislators in 25 states have introduced “second-look” bills to reconsider long sentences. Washington’s legislature, inspired by the George Floyd protests, passed a law in April to resentence more than 100 people jailed under the state’s three-strikes law. Nearly 40% of those sentenced under the law are black, ten times their share of the state’s population. That same month Maryland banned life sentences for juveniles. Since 2012 the number of lifers in America jailed for crimes they committed as children has dropped by 45%, to around 1,500.

John Fetterman, Pennsylvania’s lieutenant-governor, has made reducing incarceration a centrepiece of his campaign to win a seat in the United States Senate. He wants an end to mandatory life sentences without parole for second-degree murder, one reason why Pennsylvania has America’s second-largest population of lifers. He is taking a risk. “With every person I try to get released I’m writing my next attack ad,” he says.

World war free

Some campaigners use the courts to curb life sentences. A clutch of treaties prohibit governments from inflicting degrading treatment on anyone, including prisoners. In 2013 the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) ruled that offenders have at the outset of their sentences a right to hope for eventual release. The International Criminal Court says after 25 years sentences must be reviewed. “Twenty-five years is increasingly established in international law as the maximum minimum,” says Dirk van Zyl Smit, Ms Appleton’s co-author.

Scepticism about life sentences is spreading. In 2016 Zimbabwe’s constitutional court ruled that life sentences without parole are cruel, citing the ECHR’s decision. Belize’s court of appeal ruled unconstitutional such sentences for murder in the same year. Canada’s Supreme Court is due to decide whether a court in Quebec was right to reduce the amount of time that Alexandre Bissonnette, sentenced to life for killing six people at an Islamic cultural centre in 2017, will have to wait for parole from 40 years to 25.

Malawi may become a model for countries seeking to avoid simply replacing capital punishment with life sentences. After its High Court struck down the death penalty as mandatory for murder in 2007, the top appeal court ordered that more than 150 condemned prisoners be resentenced. (In practice, all were serving life, since Malawi has executed no one since 1992.) It directed judges to consider the circumstances of each to determine whether the death penalty should be upheld, converted to life or to a shorter sentence.

That kick-started the Kafantayeni Project, named for the case that overturned the punishment. Starting in February 2015 the High Court held hearings in Zomba, near the country’s only maximum-security jail. In cases where documents had gone missing or been eaten by termites, paralegals, law students and volunteers interviewed witnesses in search of mitigation.

Of the prisoners who have been resentenced, one was handed a life sentence but more than 140 have been released after completing shorter prison terms. To prepare the way, workers on the project fanned out to villages to explain what the ex-cons had endured and to find out whether they would be welcomed back.

One freed prisoner was Francisco James, who in 1995 was condemned to death for killing a man who was brawling with his younger brother. Immured for 20 years in Zomba prison, built to hold 800 inmates but stuffed with 2,000, he wondered whether disease would carry out the sentence that the hangman would not. He had “given up on ever getting out of prison alive,” he says. The judges decided that the murder charge was inappropriate, in part because the victim was in poor health, and freed Mr James in October 2015.

He returned to Mkwinya village in central Malawi to find that his father and brother had died, his wife had remarried and his daughter was a mother. The village chief gave Mr James a plot of land, where he grows maize, soya beans and groundnuts. By Malawian standards he is prosperous, with a motorcycle, an oxcart and two houses roofed with iron sheeting. He has fathered three more children. In April this year Malawi’s top court ruled the death penalty itself unconstitutional.

Its model is being watched in Kenya, where far more prisoners—some 4,800—may be entitled to resentencing under a Supreme Court finding in 2017 that the mandatory death penalty is unconstitutional. (In practice Kenya stopped carrying out executions in 1987.) Most of the condemned prisoners were in for “robbery with violence”. In 2019 a government-appointed task force recommended investigations like those undertaken in Malawi. To speed things up it proposed negotiations on new sentences between prosecutors and lawyers akin to plea bargains.

It is unclear how many have so far been resentenced. On July 6th this year the process hit a snag. The Supreme Court said that the mandatory-death-penalty ruling applied only to murderers, not to the majority convicted of lesser crimes. It is now uncertain if and when condemned Kenyan robbers will follow Malawians’ path to freedom, says Virginia Nelder, a member of the task force.

When liberated lifers are reformed muggers or small-time drug dealers, few will object. “History is moving towards less incarceration,” concedes Mr Lampert. Setting free those who have committed the worst crimes is harder to justify. Kenya’s reforming task force recommended keeping life sentences without parole for them.

After his daughter Tijana was murdered Igor Juric attended trials of other abusers and came to the conclusion that “we, as a society, have to do something to remove killers from our social circles, and keep them far away from children.” “Protection of our children” matters more than “conventions and laws of countries that I don't even live in”, he continues.

That view is understandable. But anyone who meets Mr Clemons will find it hard to fear all ageing lifers or fail to consider their humanity. He reckons he can succeed as a baker “in the free world”. At 62, he says, “I’m gonna work my way up.”

© The Economist Newspaper Limited, London, 10th July 2021