February 21, 2025, by Chloe

Nottingham old and new

Charles Deering’s ‘Nottinghamia vetus et nova’, which translates from the Latin to ‘Nottingham old and new’, is widely considered to be one of the earliest histories of the town. First published in 1751, the book is a key source for the early study of Nottingham’s caves.

Deering was born in Germany and spent his adult life travelling between England and France before settling in Nottingham in 1736, where he would remain until his death thirteen years later. He certainly seems to have developed a passion for his newfound home, as he took on the considerable task of editing copious materials and notes gathered by local politician John Plumptre to create ‘Vetus et Nova’, which was ultimately published posthumously in 1751.

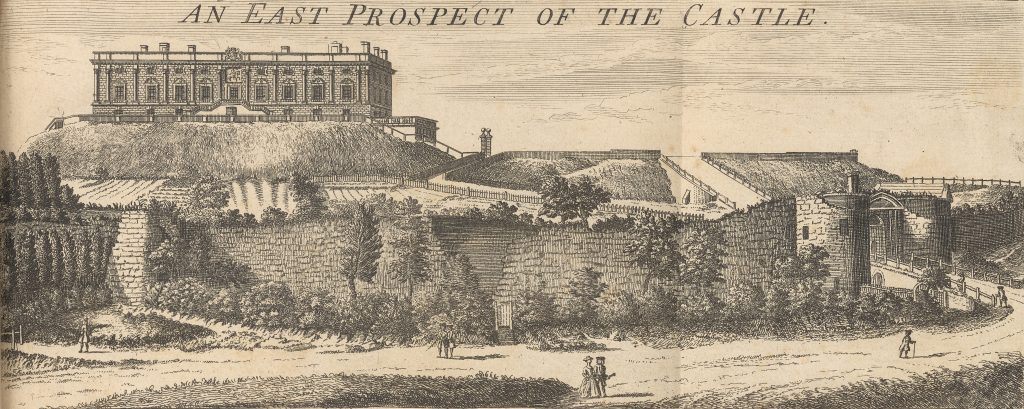

East prospect of Nottingham from ‘Nottinghamia vetus et nova’ by Charles Deering, M.D; 18th century. University of Nottingham, East Midlands Special Collection, Not 3.D14 DEE.

He was particularly effusive on the subject of the Park, describing its famous rock holes as ‘the ruins of an ancient pile of building not erected upon, but cut and framed in the rock, concerning which, for want of any written account, various have been the conjectures of the learned in antiquities’. He goes on, in his own extensive account, to take sledgehammer to several of the theories proposed by other writers. For instance, he dismisses out of hand William Stukeley’s view that the rock holes were the remains of a ‘colony’ of ancient Britons, claiming that the regularity of the excavations indicates Saxon or later habitation. He poked further holes in Stukeley’s imagining of a verdant ancient cliffside settlement fed by the Leen by positing that the path of the that river in modern times followed an artificial diversion created to supply the Castle in the period following the Norman conquest, and that therefore any earlier inhabitants would be quite some distance from a source of water. On this second point at least, subsequent scholarship has proved Deering right.

Engraving of rock holes in the Park, from ‘Nottinghamia vetus et nova’ by Charles Deering, M.D; 18th century. University of Nottingham, East Midlands Special Collection, Not 3.D14 DEE.

As for their later history, Deering reports that, in his own time, the rock holes are equally commonly known as the ‘popish houses’ and that there is still a cultural memory of the destruction of some of these structures by Parliamentarians during the civil war, presumably due to their link with monasticism. He broadly accepts that the rock holes had been home to ‘a monastery with anchorites’ but is less confident in associating them with any particular order, rejecting out of hand the prevailing theory (then and now) of a connection with Lenton Priory. Indeed, he dismisses the site today known as Lenton Hermitage as unfit for human habitation, instead postulating that it would have been ‘very well suited for a stable to shelter a cow or two’!

Engraving of the inside of a rock hole in the Park, from ‘Nottinghamia vetus et nova’ by Charles Deering, M.D; 18th century. University of Nottingham, East Midlands Special Collection, Not 3.D14 DEE.

His lack of enthusiasm for romanticism extends to the so-called Mortimer’s Hole, which he identifies has being a rock-cut staircase beginning ‘from the court of the old tower’ and leading ‘through the body of the rock to the bank of the river Leen’. Whether the passage upon which he bestowed this famous moniker ever had any association with Roger Mortimer, Edward III or even the fourteenth century in general continues to be a matter of considerable controversy, but Deering himself had few doubts. Instead, he directs his sceptical gaze at the stories which were circulating about the space in his lifetime.

Engraving showing East Prospect of Nottingham Castle, from ‘Nottinghamia vetus et nova’ by Charles Deering, M.D; 18th century. University of Nottingham, East Midlands Special Collection, Not 3.D14 DEE.

In a slight departure from the now-canonical version of the legend, he explains that many people believe that the tunnel earned its name from its use as a a means for Mortimer to sneak into Queen Isabella’s chambers unseen. However, he has no time whatsoever for this explanation, stating that Mortimer’s prominent role in the regime running the kingdom during the young king’s minority would have ‘furnished him with frequent opportunities of going publickly to her’: no need for secret passages. Bizarrely, he also commented that the passage, which is a continuous staircase, would have been a sufficiently uncomfortable place for Mortimer to await the Queen’s company that it couldn’t possibly have been used for this purpose! Instead, he gave more weight to the now more familiar version of the story, in which a teenage Edward III used the tunnel to capture the renegade Mortimer, perhaps helping to solidify it in the public imagination.

If you’d like to find out more about the rock holes in the Park and at the Castle, why not check out ‘Tales from the Caves’, which is running in the Weston Gallery at Lakeside Arts, Nottingham until 9 March 2025? Learn more on our website!

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply