Duckweeds represent a fascinating case of organ loss during evolution. This phenomenon is more commonly studied in animals, including limb loss in snakes and vision loss in cavefish. The wholesale loss of multiple structures sets duckweeds in a league of their own for investigating organ loss, with the most extreme example, Wolffia, completely lacking roots and vasculature tissues. We are using a combination of molecular biology, transcriptomics, phenotyping and physiology to investigate the molecular changes and physiological adaptations associated with organ loss in duckweeds.

Our Students

Claire Smith

I became fascinated by the interplay of regulatory networks in plant development during my Bachelor’s in Genetics at the University of Leicester and after doing my Master’s in Developmental Biology at the University of Bath, I joined the BBSRC DTP here at the University of Nottingham in 2021 as part of the Yant and Bishopp groups.

Over the course of evolution, duckweeds have undergone a reduction in body plan complexity, including the loss of the ability to grow roots, and have had a loss of protein coding genes. My PhD project investigates a potential connection between loss of roots and the loss of key hormone signalling components. I use bioinformatics, physiological studies, and transcriptomics in my work.

Rebecca Fairburn

My name is Rebecca, and I am currently working to complete my PhD at the University of Nottingham, funded by the BBSRC Doctoral Training Partnership. Before my PhD, I also completed my integrated master’s at the University of Nottingham, graduating in 2023 with a first-class degree in Plant Science. It was during this undergraduate degree that I developed a fascination with plant evolution and was introduced to the potential of duckweed as a model plant.

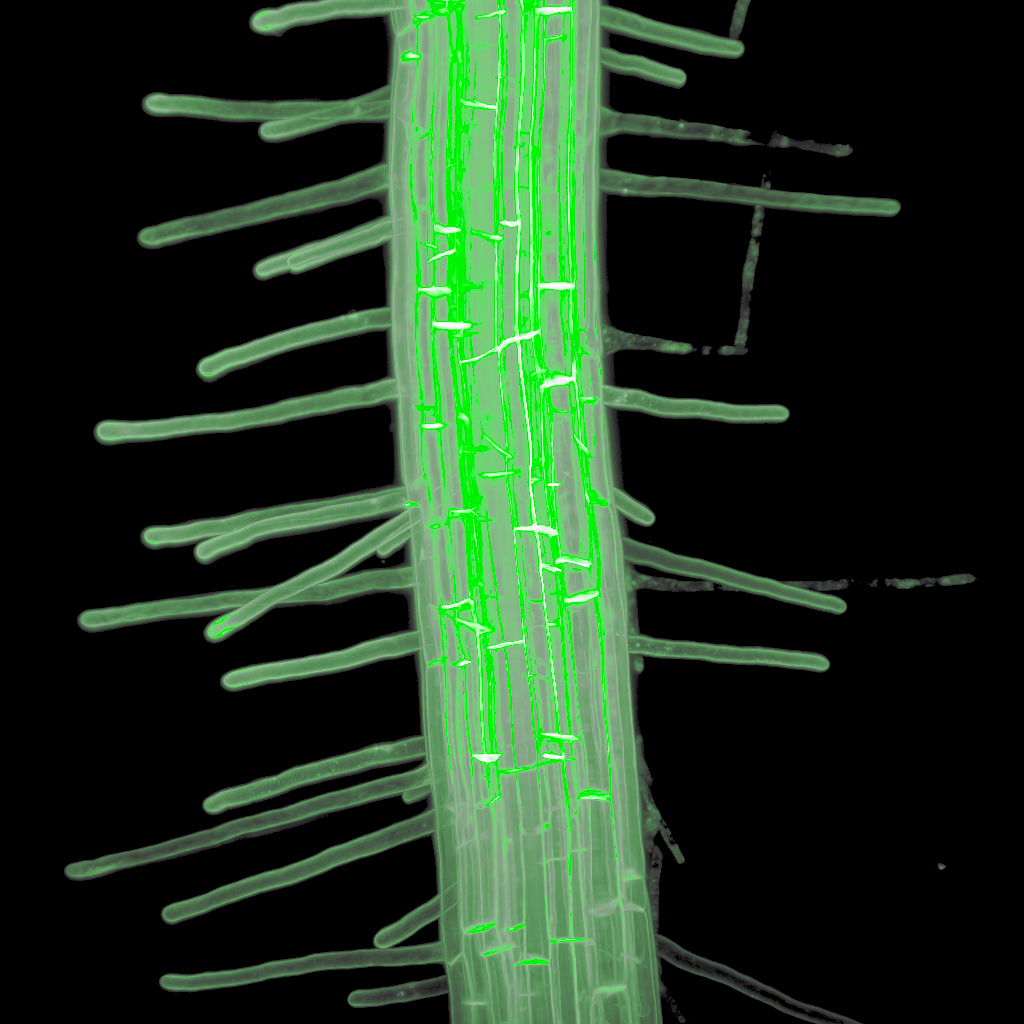

In land plants, root hairs (shown in the photo) are an important trait that allow for the increased uptake of nutrients and water. In duckweed, root hairs are absent. My project aims to reengineer the root hair pathway in duckweed, resurrecting a trait lost for millions of years.

This project will provide us with a unique opportunity to gain insight into how structures and traits and the networks which encode them are lost or reduced over time, allowing us to unpick the complex genetic pathways that determine vestigialisation or organ loss.