Early Years

Growing up in Eastwood, which depended almost completely on the mining industry – ten pits lay within walking distance – was difficult for a boy like Bert Lawrence, often in poor health and obviously frail. He was bullied at school, he failed to join in games with the other boys and (still worse) clearly preferred the company of girls, who talked rather than fought. School had its own problems for him, of isolation and difference: 'When I go down pit you'll see what –––– sums I'll do' was the constant refrain of his contemporaries, and Lawrence knew from very early on that, in spite of his father's expectations, he would not be a miner. It took him some time to do well at school: he felt the pressure of being unlike the other boys, and he was following his elder brother William Ernest, who had excelled in everything he did, whether school-work or games-playing. By the age of 12, however, Lawrence was doing well; he became the first boy from Eastwood to win one of the recently-established County Council scholarships, and went to Nottingham High School.

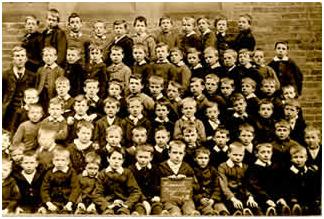

Lawrence, second from left, third row from top,

with classmates at Beauvale Board School (Lawrence Collection)

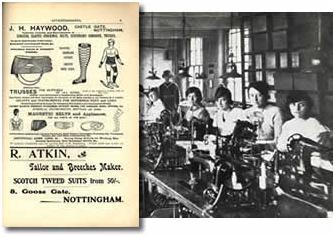

At the High School, however, he did not distinguish himself. The scholarship boys were a class apart; Lawrence made few friends, and after an excellent start his performance fell away (not helped by the notoriety necessarily brought on his family by his father's brother Walter being arrested in 1900 for killing his 15-year-old son); and Lawrence left school in the summer of 1901 with little to show for the experience. He started work as a factory clerk for the Nottingham surgical appliances manufacturer Haywoods, but that autumn a catastrophe overtook the Lawrence family. William Ernest, by now a successful clerk in London, fell ill and died. Lydia Lawrence was distraught; she needed her children to make up for the disappointments of her life. When Lawrence himself went down with pneumonia that winter, her affections turned significantly towards him; and when he recovered it was to start work as a pupil-teacher at the British School in Eastwood, where he spent the next three years.

Haywoods factory and advert (Lawrence Collection)

Another important development was his acquaintance with the Chambers family, who had recently moved from Eastwood into the country. He and his mother visited the Haggs Farm in the summer of 1900, and Lawrence began regular visits there after his illness: he became a particular friend of the eldest son Alan. The second daughter Jessie, however, made herself his intellectual companion; they read books together and endlessly discussed authors and writing. It was under Jessie's influence that in 1904 Lawrence started to write poetry. 'A collier's son a poet!' he remarked sardonically, but his mother had written poetry in her time. In 1905 he started his first novel, eventually to become The White Peacock. Jessie Chambers saw all his early writing; her encouragement and admiration were crucial.

In 1904 Lawrence had done extraordinarily well in the King's Scholarship examination, achieving the first division of the first class, and his mother was determined that he should study for his teacher's certificate at the University College of Nottingham. After a year's full-time teaching in Eastwood, to earn what he could, he went to Nottingham in 1906 to follow the Normal course. He completed its demands without difficulty, acquiring a considerable contempt for academic life while doing so; more importantly (for him) he completed a second draft of his novel, as well as entering three stories in the 1907 Nottinghamshire Guardian Christmas story competition: 'A Prelude' won, under the name of Jessie Chambers. Qualified in 1908, he took a post in an elementary school in Croydon, and moved to London. He was now reading significantly modern authors such as William James, Baudelaire and Nietzsche (whom he discovered while in London), and during these years he lost his religious faith.

© Professor John Worthen, 2005

Next chapter: School Teacher