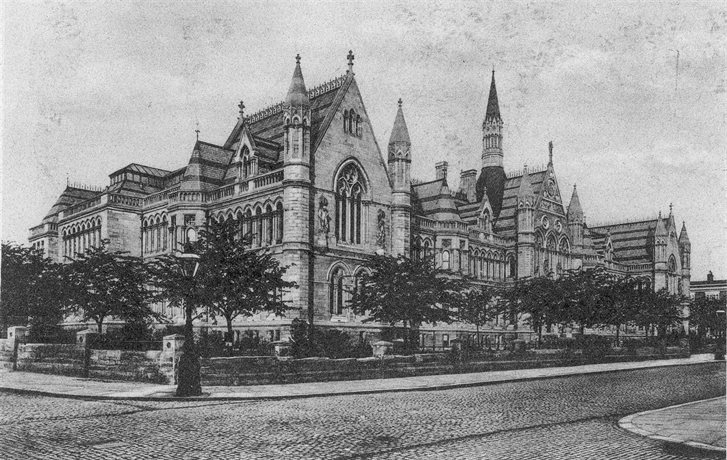

Arkwright Building, University College Nottingham, 1987

Arkwright Building, University College Nottingham, 1987

This guest post is written by Dr James Dawkins, Research Fellow, Nottingham Universities and Historical Slavery.

In November 2019, I began working at the University of Nottingham on a project entitled Nottingham Universities and Historical Slavery. It’s a collaborative study between the University of Nottingham and Nottingham Trent University in which I’m tracing their historical connections with transatlantic slavery. More specifically, I’m examining the nature and extent to which these two institutions were connected to, benefitted from, and also challenged British colonial slavery.

Although both institutions were founded in the 20th century, there is a common starting point in the heart of the City of Nottingham dating back to the late 18th Century.1 During this period, Nottingham’s famous historical lace and hosiery industry drew on supplies of raw cotton produced and cleaned by enslaved people of African descent who laboured on plantations in the American South and elsewhere in the Americas in the early 19th century.2

Several significant links to this period are currently under investigation including the University of Nottingham’s connection to the Bentinck family (Dukes of Portland). Previous research by Haggerty and Seymour – Slavery Connections of Bolsover Castle, 1600-c.1830 and ‘Imperial Careering and Enslavement in the Long 18th Century: The Bentinck Family, 1710-1830s’ – highlights that the 1st Duke owned at least one plantation and enslaved Africans in Jamaica where he was Governor in the 1720s. The 3rd Duke was silent in the face of abolitionist lobbying over the infamous Zong case while prime minister in 1783 and stood in defence of colonial slavery in his role overseeing Britain’s colonies in the 1790s. He and his son, the 4th Duke, a professed opponent to abolition of the British slave trade, also supported members of their wider family who were colonial officials, plantation holders and owners of enslaved Africans in what is now Guyana. Between the 1920s and 1940s, the family gifted a considerable sum of money to University College Nottingham (the forerunning institution to the University of Nottingham and Nottingham Trent University), and later donated their dynastic papers to the University of Nottingham archives in lieu of tax. The 7th Duke was appointed as the Chancellor of the University of Nottingham in 1954 and held this position until 1971. He was also memorialised, in 1956, via the opening of two new campus constructions – the Portland Building and Portland Hill road.3 These are important links which the University of Notitngham will be reviewing in order to think through how it can best acknowledge its connections to transatlantic slavery.

My research is being steered by a group which includes academics and other staff from the two universities and members of Nottingham’s African-Caribbean Community. So far, I have generated a comprehensive list of 852 donors to University College Nottingham and later the University of Nottingam between 1875 and 1960. A number of these include individuals and businesses with known direct and indirect historical connections to transatlantic slavery, such as the Bentincks, Barclays Bank and Algernon Henry Strutt, 3rd Baron Belper. There are also several buildings, rooms and roads, across the campuses of both universities which bear the names of families linked to slavery, which include the Arkwright Building and Bentinck and Tissington Rooms. I’ve now moved into the second phase of the study and am investigating the backgrounds of the University of Nottingham’s donors in order to discern whether or not more of them were connected (directly or indirectly) to Britain’s transatlantic slave economy.

In addition to this historical research, people in Nottingham will be given a chance to get involved in related community engagement events. This will include a session in which recommendations for reparatory justice are collectively produced and discussed for the purpose of guiding the city’s universities towards the sensitive and appropriate acknowledgement of their links to transatlantic slavery. The project is scheduled to conclude in May 2021 with an official report being published which contains both the findings from this historical study and recommendations for reparatory justice.

The study emerges out of the wider reflective historical research that is taking place at American and British universities which are investigating their origins and links to transatlantic slavery. It also follows on from research already taking place at the University of Nottingham on historical slavery, along with the race equality initiatives currently being pursued by the institution. These include the establishment of the Institute for the Study of Slavery (ISOS) in 1998 and the university’s forthcoming application for bronze Race Equality Charter (REC) status. The UoN has also joined the international Universities Studying Slavery group which supports participating institutions in the exploration of their complicated historical connections to transatlantic slavery and addressing its contemporary legacies.

I am pleased that the University of Nottingham has taken the important decision to critically examine and acknowledge its connections to transatlantic slavery. This is a significant step in its endeavour to identify and dismantle the legacies of slavery, namely institutional racism, which continues to disadvantage its black and brown staff and students. In doing so, the University is continuing to move towards the creation of a more welcoming, equal, diverse and inclusive environment where all ethnic minorities can thrive, particularly those of African and African-Caribbean heritage.

1. John Beckett, Nottingham: A History of Britain’s Global University (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2016), pp. 12-39.

2. Susanne Seymour, Lowri Jones and Julia Feuer-Cotter, ‘The Global Connections of Cotton in the Derwent Valley Mills in the Later Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Centuries,’ in Chris Wrigley, ed. The Industrial Revolution: Cromford, The Derwent Valley and the Wider World (Cromford: Arkwright Society, 2015), pp. 150-170.

3. Beckett, Nottingham., p. 108.