Authentication of legal and administrative documents

In order to understand a medieval document, researchers need to know what it is, and why it was created. Catalogue descriptions created by archivists or curators will give you some information about the document. However, many documents have not been described in detail so you may have to do your own detective work.

Deeds and other formal documents used stock phrases and formulas to convey legitimacy. They also used authentication devices to persuade people that they were genuine, and could be relied upon as evidence. Historians study the form and content of documents to determine whether they were written according to the conventions of the time they are said to come from. Some documents have been discovered to be later forgeries by using this method. Common deed forms are described in detail in the Deeds in Depth unit.

Seals

Seals were the only form of personal authentication in the Middle Ages. Deeds were not usually signed until the sixteenth century. The earliest example known in our collections is Mi D 1124 (dated 1466), signed by John Byngham. Some medieval signatures exist in private letters, but many letters were written by scribes from dictation so the name at the end of the document may not actually have been written by its owner.

A seal is an impression made by pressing a wood or metal matrix into warm wax. The pattern on the matrix is transferred to the wax. Seals come in various shapes and sizes, and there are a number of ways of attaching seals to documents.

The monarch used (and still uses) the Great Seal of England to seal important state documents and letters patent. Each monarch had a different seal, but they all look similar. Below is an example of King James I’s Great Seal from 1623 but earlier Great Seals look much the same.

King James I’s Great Seal, 1623 (Ne D 3846)

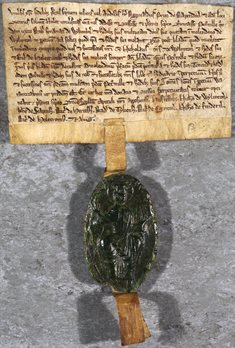

Next is an example of a large ecclesiastical seal in green wax from 1230. Religious individuals and institutions used this pointed oval shape, which is called a vesica seal. The seal hangs from the bottom of the document and is therefore called a pendant seal. It has different impressions on the front and back. The front side is the seal of the chapter of Repton Priory in Derbyshire, and shows Christ in majesty, raising his right hand in blessing, and holding a book in his left hand. On the back there is a smaller counterseal showing the Madonna and child, and the Latin words ‘Sigillum Reginaldi Prioris Rependun’ (‘the seal of Reginald, Prior of Repton’). The back side shows evidence of fingerprints, suggesting that the seal was formed by hand around the parchment tag. The front side is flatter because the seal matrix was big enough to cover it when pressed down.

Seal of the Chapter of Repton Priory, and of Prior Reginald, 1230 (Po 126)

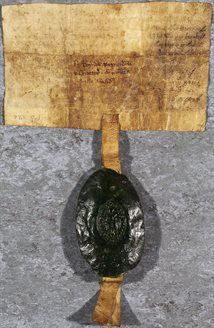

Noble women also used the vesica shape for their seals. Below is the seal of Matilda de Nevill, sister of John de Eyvill. It authenticates a deed which was probably made c.1275-1300. The seal, in red wax, shows a standing woman holding a bird of prey. The words ‘Matilda de Nevill’ are written around the edges. It it is attached to the deed by an original textile thong, probably made of silk.

Seal of Matilda de Nevill, c.1275-1300 (Me D 4/5)

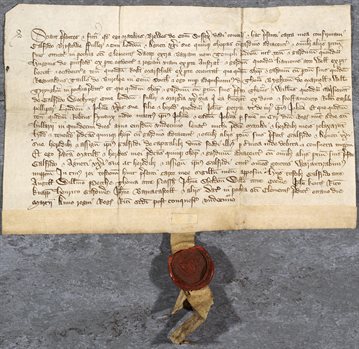

The following deed from 1388 was also made by a woman, Maude Brewes, but the seal is small and round, like most personal seals. Small seals like this could have been made with a hand-held matrix, or by a matrix attached to a ring (a signet ring). The matrix has transferred the impression of a coat of arms, but it might not be unique to Maude or her family since by the later Middle Ages it was possible to buy ready-made ‘personal’ seals.

Seal on title deed from 1388 (Ne D 4716)

Some deeds were made by more than one person, and were therefore sealed by each of them. This example from 1452 was sealed by six people, although one of the seals has since broken off.

Title deed with six seals, 1452 (Ne D 4662)

All of the examples above are of seals attached to open, public documents. Below is a letter of attorney from 1428, which has a seal attached to a tongue of parchment cut from the document. A further narrow tongue has been cut for use as a wrapper. This indicates that the document was intended to be folded and tied and then transported for personal and private delivery to the attorney.

Letter of attorney, 1428 (Ne D 949)

Dates, witnesses and scribes

Matilda de Nevill’s deed (shown in full in the Wives, Widows and Wimples resource) is an example of authentication by witness and seal only. Deeds up to the mid-fourteenth century were often not given a date. The date has to be estimated from the style of the document, the handwriting, and the known life dates of the people named in it. Her deed was witnessed by nine people, some of whom are mentioned in other documents of a similar date. The Dating Documents unit gives hints on how to go about determining the date of undated documents.

The scribe of a particular deed is occasionally named as a witness. This is quite rare, but instances do survive in The University of Nottingham’s collections, such as in Mi D 27 and Mi D 236.

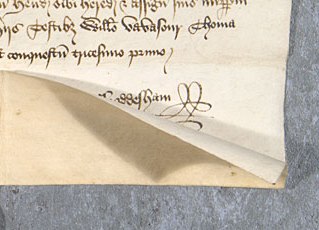

We do not usually know the name of the scribe, but occasionally he or she left identifying marks. The name ‘Froddesham’ is written with a flourish, hidden underneath the flap of this beautifully-written deed from 1452. This is perhaps Thomas Froddesham, who was a member of the Company of Scriveners.

Signature of 'Froddesham', detail from Ne D 4662

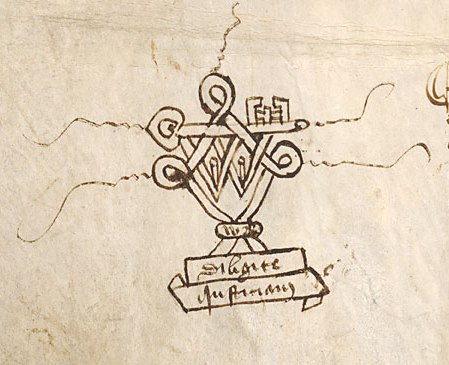

The only other person who might leave a mark on a formal document would be a notary - a type of lawyer. Under Roman law notaries were required to authenticate documents. This is still the case in many European countries. They were not normally needed in England and Wales because customary law meant that anyone could authenticate their own documents using seals. However, the church used Roman law, so occasionally notarial instruments relating to church business can be found in UK record offices. This example from 1518 shows a typical mark, each of which was unique to a particular notary.

Notary's mark used by William Brodhed, notary public in the Diocese of York (Ne D 1914)

Many deeds are ‘given at’ a particular place (the Latin word used is ‘Datum’). For example, Maude Brewes’ deed is given in the parish of St Clement Danes in London. This evidence could be used to spot a forgery if it was known that one of the parties was elsewhere at the time.

Chirographs

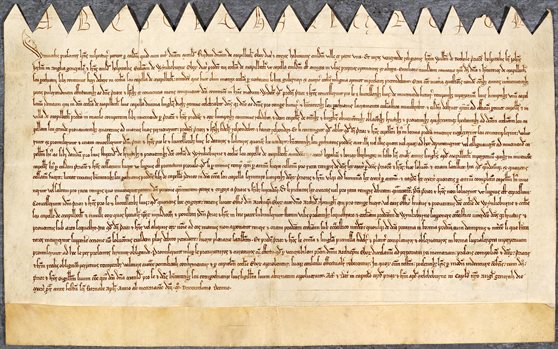

Deeds known as indentures are characterized by a wavy or spiky top edge. They were devised so that two people making an agreement could each keep a record of what was decided, and could prove that they had a genuine copy. The deed was drawn up twice on one sheet of parchment, which was then cut in half. If the pieces matched, the deeds could be seen to be authentic. Often words or letters were written across the area which was to be cut, to strengthen the authenticity. In the example below, the letters of the alphabet have been used, but often the word ‘Chirograph’ was used (literally meaning ‘handwriting’ in Greek).

Chirograph agreement relating to the rectory of Maplebeck, Nottinghamshire, 1310 (Ne D 2214)

Endorsements

Descriptions and explanations of the content of medieval deeds were often written on the back by later readers or cataloguers. They were not usually written when the deed was drawn up. They are usually very informative, and save you having to read the whole document yourself. However, they can sometimes be inaccurate so they should be treated with caution. If you have any doubts, read the document yourself or consult an expert.

Cancelled documents

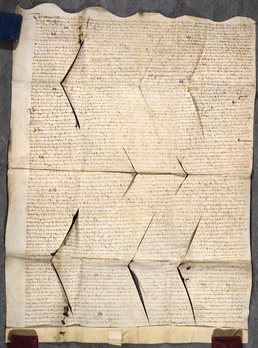

If a deed or document was not needed any more (perhaps because a lease or an agreement had come to an end), but was still kept in the archive for reference, it could be made void. This would make it clear to anyone that it was no longer in force. Deeds could be voided by any of the following methods:

- Obliteration - blacking out the text with ink

- Cancellation - drawing a mesh of diagonal lines across the text

- Cutting - making herringbone cuts through the body of deed by folding it in half and cutting diagonally

- Removing the seal – deliberately cutting away the seal and seal tag

Cancelled marriage settlement, 1520 (Ne D 1915)

Next page: Ownership and provenance