Buildings and Bibles

The state of parish churches was a major concern for the Archdeaconry court throughout its history. Rectors, including lay rectors, were generally responsible for the upkeep of chancels. Sir William Cavendish of Welbeck Abbey - later Marquess and Duke of Newcastle - was a particularly bad offender, presented for neglect of Cotham's chancel between 1618 and 1624, and Car Colston's during the 1660s.

Other repairs and the provision of furnishings and books were the responsibility of the parish, through the churchwardens. The Archdeaconry archive contains many references to failures in these duties. Sometimes it was shown that even the basic provision of a Bible had been neglected.

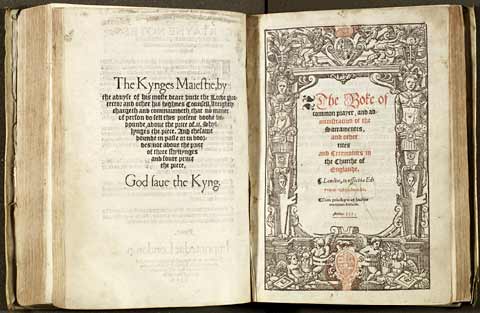

One of the items required by every parish was a Book of Common Prayer. This went through a number of editions in the mid-sixteenth century, reflecting changes in religious policy, and it was important to have the right version. Other fittings took time to procure and to mount on church walls, such as the boards which displayed the ten commandments or the permitted degrees of marriage (identifying when it was unlawful to wed somebody within a family connection).

Maintenance of ancient church buildings is still a problem today, but even issues which we may think of as modern are reflected in the seventeenth-century records. For example, Winthorpe church stood 'in the fields and remote from company', and a fear of theft and vandalism prompted the churchwardens to keep all the church books and valuables in a house in the village (AN/PB 295/7/191).

'Towers and Spires', from John T. Godfrey, Notes on the Churches of Nottinghamshire: Hundred of Rushcliffe (London: 1887) from Not 1.M14 GOD

Screveton and its Steeple

Screveton Parish Church, from John T. Godfrey, Notes on the Churches of Nottinghamshire: Hundred of Bingham (London: 1907) from Not 1.M14 GOD

An extensive series of Presentment Bills from Screveton parish illustrates how major church repairs could drag on for years.

In 1596 the churchwardens reported that their steeple was 'in decay'. In 1603 they hoped to finish the work in the next year. By 1614, despite expenditure of over £100, the steeple was still not 'brought to that perfection which we desire'. Meantime, the churchyard could not be fenced, nor the bells properly hung. By 1621 the churchwardens were blaming the mason, Christopher Gascoine of Nottingham, for letting them down.

The work was still being done 'as fast as we can' in 1624, and appears to have been finished by Easter 1625, although the bells were still not hung. The story ends in Easter 1626 when the churchwardens reported that 'our bells are not as well hung up as we intend they shall be', but that the work was due to be completed by August.

Religious books

This 1552 edition of the Book of Common Prayer took a more extreme Protestant line than the 1549 version, and provided the basis for Queen Elizabeth's 1559 revision and later editions of the seventeenth century.

Book of Common Prayer (London, 1552) Pw V 76

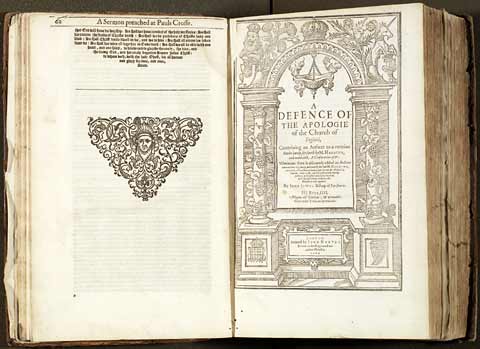

In 1609 a collection of the complete works of John Jewel (1522-1571), Bishop of Salisbury, was published. This became one of the books, along with Erasmus's Paraphrases, which churchwardens were supposed to provide. In 1613 a number of parishes reported that they did not have a copy. The churchwardens of Staunton explained that they had been disappointed by the default of the carrier (AN/PB 295/4/46).

The Works of the Very Learned and Reverend Father in God John Jewell (London, 1609) Spec. Coll. Queen Elizabeth School Library

Bibles for churches were supposed to be 'of the largest volume', and were costly to buy. The churchwardens of Shelton claimed at Easter 1616 that they did not have a 'King's Bible' (the King James Bible of 1611) because they had been 'at very great charges about the repair of the church' in the past year. They made a collection, and were given a few months in which to complete the purchase (AN/PB 295/6/12).

Church finances

Repairs to church buildings, then as now, were extremely expensive. The parish of Edwinstowe, faced with an estimate of £300 - which would 'certainly tend to the ruine of all or most of us Petition[er]s' - asked the Duke of Newcastle, Lord of the Manor, to help them procure £200 worth of wood promised from the royal estate at Birkland and Bilhagh. The petition, shown below, was signed by the vicar, William Silverton, and fifteen other parishioners.

Petition of the inhabitants of Edwinstowe, Clipstone and Budby to Henry Cavendish, 2nd Duke of Newcastle upon Tyne, [no date, 1681-1691] Pw 1/284

Charitable donation to meet overseas disaster is not entirely a modern phenomenon. Parishioners in the seventeenth century were regularly asked to assist other congregations, both in Britain and abroad. When the new Puritan colony in North America needed help, there was a collection for Virginia in 1616; another item in John Tibberd's account book (AN/AC 1/1) shows support for 'the French Protestantes'.

Householders were required to contribute money towards their church buildings and fittings, by means of 'lays' or 'assessments' based on the value of their property. Refusal to pay brought them before the court. In 1612, a Presentment Bill (AN/PB 295/3/97) reported that a number of Mansfield parishioners had defaulted in payment for 'the repare of the bellfraye [belfry] & the castinge of three of owr bells'. Thomas Innocent, assessed at 30 shillings, was the main debtor.

Churchwardens' duties

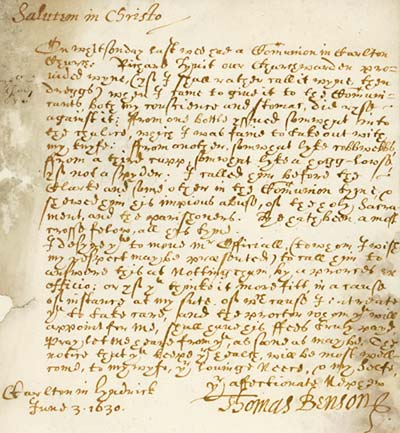

At Whitsunday 1630, the churchwarden Richard Huit failed spectacularly in his duty to provide wine and bread for Holy Communion. The rector, Dr Benson, described him to the court as 'a most crosse felow', and explained,

…Richard Huit our Churchwarden provided Wyne (yf I shall rather call it wyne, then dreggs) when I came to give it to the Communicants, both my conscience and stomac did ryse against it; from one bottle yssued somwhat into the chalice, which I was faine to take out with my knyfe. From another, somewhat lyke a cobbwebbs, From a third cupp, somwhat lyke a hogg-louse, yf not a spyder…

Huit subsequently appeared in court. The Act Book (AN/A 40) records his plea 'that he did get the bottles cleane washed and that he is very sorry that such thinges happened to be in the wyne'.

Presentment Bill relating to Richard Huit, Carlton-in-Lindrick parish, 1630 AN/PB 340/1/53

Next: Controlling the Community