Controlling the Community

'Playing at Football', in Andrew W. Tuer, Pages & pictures from forgotten children's books (London, 1898-1899) from Briggs Coll. PZ 6/P2

In the seventeenth century, the parish church was at the very centre of community life. Those who did not attend on Sundays and holy days risked a fine of 12d.

Church gatherings brought all sorts of people together, and the records of the Archdeaconry court show people fighting for seats, turning up drunk, allowing children to run around and cry, arguing with the minister or churchwardens, and larking around on consecrated ground.

Whether recreations could be enjoyed at any time on the Sabbath was hotly-debated. Sunday was for many people the only day when freedom from labour provided the opportunity for games and sports.

Parishioners reported to the church court for 'Sabbath-breaking' were shown to be enjoying a variety of community entertainments, ranging from simple gatherings in the alehouse, games of 'nine holes', quoits and bowling, to music, dancing and theatricals.

In 1637 John Sprigg of Tuxford, for example, hired a musician, Thomas Haggs, to play in his house, and was presented for allowing young people to dance there while a church service was going on (AN/PB 341/4/45).

Illustration from the ballad 'Cherry Cheeked Patty for Me' (Belper, 19th century) from Spec. Coll. Oversize Ballads II : PR 1181.B2

Local communities, despite their Christian beliefs, sometimes showed faith in 'wise people' who claimed to be able to foretell deaths and identify thieves. Their methods now seem bizarre - for example, spinning a sieve on a pair of shears.

In 1623 there was concern about a craze for visiting the 'stroking boy of Wysall', whose touch allegedly could bring miraculous healing 'contrary, as [we] are persuaded, to God's word and the ecclesiastical laws' (AN/PB 297/11). Most mentions of witchcraft in the Presentment Bills relate to such local superstitions. Sorcery involving harm to others was a more serious offence and was dealt with by the civil authorities.

Sabbath breaking

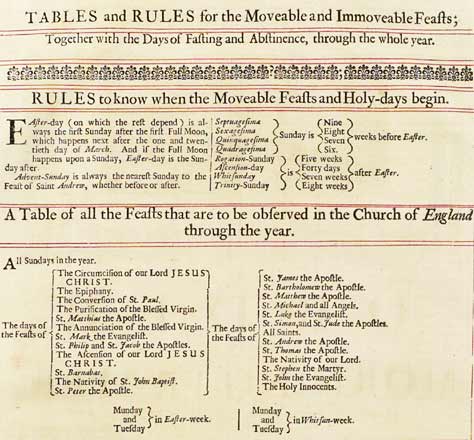

Table of feasts, holy days and days of fasts and abstinence, from the Book of Common Prayer (Oxford, 1681) from Mi LP 45

Some Puritans were hostile to the pursuit of any leisure activities on Sunday. To counter the effects of such fanaticism, King James issued his 'Declaration of Sports', which was published in 1618 as 'The Book of Sports'. This acknowledged the value of allowing working people to enjoy healthy exercise on Sundays, and the danger that otherwise 'filthie tiplinge & drunkennes' would take its place.

A common misconception, shown here in a later illustration, held that King James's 'Declaration of Sports' licensed all Sunday recreations. In fact, it allowed only some games and sports, and only after service had ended. People who had not gone to church were excluded from these benefits.

'Keeping Sunday' according to King James's Book of Sports, from Cassell's Illustrated History of England, iii (London, 1864) from Spec. Coll. Not 1.W8 HOW/W

It was not only alcohol or entertainments which took people away from church. Some occupations prompted parishioners to work on Sundays, especially at harvest time.

Although by the early nineteenth century people were no longer required to attend the parish church every Sunday, the concern about 'Sabbath-breaking' remained strong for many religious communities. It has been voiced most recently in opposition to Sunday shop opening.

The Sabbath Breaker Reclaimed, or, A Pleasing History of Thomas Brown (London, 19th century) Spec. Coll Pamphlet PR 978.L6

Community activities

Staunton parish church, showing its bell tower from Transactions of the Thoroton Society, XXVII (1923)

Frequent presentments to the court for 'drinking or keeping company' on Sundays or holy days illustrate the temptation of beer around a warm fire, as opposed to a long sermon in a cold church. But drunkenness could lead to disorder in the church itself: Lawrence Heath did manage to turn up for service in Tuxford in 1631, but was so inebriated that he was sick in the church (AN/PB 340/4/51).

May Day events, inspired by ancient pagan rituals, were regarded with increasing suspicion as Puritanism gained strength. In fact, the church authorities only had cause to complain if celebrations on a Sunday or holy day took people away from church services. Thus, in 1608, thirty-five people from various parishes were cited for being at a football game on May Day when they should have been at church (AN/A 16).

The church and churchyard were convenient places for youths to gather, prompting complaints about their behaviour. An unusual episode, with a sad outcome, was reported after Lent 1630 by James Read, clergyman at Staunton-in-the-Vale.

He described how Thomas Richardson, blacksmith, the ringleader of 'a tumultuous company of rude servants', picked the lock of the belfry, and for three weeks rang the bells each evening, sometimes until very late. Tragedy struck on Easter Monday, 29th March, when,

…having runge from day-breaking, w[i]th clamourous rudenes ill beeseeming that place, in the after-noone certaine maidens were gotten in among them: one of w[hi]ch being by a stander-by cast on a bell-rope, shee was daungerously plucked up by the feet, & fell uppon her neck & shoulders: & was carried out senceles.

The young woman had not recovered, more than two weeks after the event. Richardson appeared in court on 26th May, and was required to acknowledge his guilt publicly (AN/A 40).

Presentment Bill relating to Thomas Richardson and an accident in the bell tower, Staunton parish, 14th April 1630 AN/PB 328/1/34

Personal relationships

Illustration from the ballad 'The Devil's in the Girl' (19th century) from Spec. Coll. Oversize Ballads II : PR 1181.B2

Extramarital sexual relationships often came before the court, which was concerned both about Christian morality and the social problems of illegitimacy.

Salacious details abound: Elizabeth Smyth of Lound, an alehouse-keeper, was commonly known as 'Few Clothes' and was reported in 1610 to have committed adultery with two men - one a wife beater and wizard - and to have had an illegitimate child by a third (AN/PB 296/1/3).

Meanwhile, in Normanton-on-Trent in 1626, a Walter Garlick, who was separated from his wife in Wiltshire, was living 'lasciviously'. He boasted that he could have fourteen women at his pleasure! (AN/PB 326/10/17)

Domestic violence and the arguments of neighbours could come before the church courts. Thus, in 1634 Robert Haslape of Kelham came home drunk and beat his wife in time of divine service (AN/PB 328/7/20), while Agnes Ridge of Winthorpe, rebuked by her mother-in-law in 1624 for receiving disorderly persons into her house, called her 'old rade' and threw stones at her (AN/PB 326/6/42).

Clergymen were not always the best examples to their parishioners. In 1634, Mr Thomas Holden, the curate of Lambley, was accused of striking one parishioner, brawling with another in the church, quarrelling with others, haunting alehouses and living in adultery (AN/PB 303/309).

Next: Book of Common Prayer