Belief and Persecution

The late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries were times of nationwide religious turmoil, reflected locally in the records of the Archdeaconry of Nottingham. One of the functions of the court was to enforce adherence to the Elizabethan religious settlement. This meant combating Roman Catholicism on the one hand, and extreme Puritanism on the other.

'Popish recusants' (as Catholics were commonly described) were regularly reported to the Archdeaconry court. They were often excommunicated, after refusal to appear to answer the charges against them. This barred them from the Anglican ceremony of holy communion - a punishment unlikely to concern committed Catholics. Questions about recusancy were still asked by the Archdeacon in the early eighteenth century, but by then the churchwardens rarely took action.

Catholicism was punishable as a civil as well as an ecclesiastical offence from 1593, and remained so throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. There was a powerful political dimension. As the plots in favour of Mary Queen of Scots had demonstrated, adherence to the Catholic faith might be associated with treason, and this fear continued to influence government policy during the Jacobite conspiracies of the eighteenth century.

The extent to which dissenting Protestant sects were persecuted varied over time: there was an effort to stamp out Separatism in the first decade of the seventeenth century. Following the Parliamentarian victory in the Civil War of the 1640s, the Anglican church system was abolished. Non-conformity was outlawed again in the 1660s, affecting groups of Baptists, Independents and Quakers, but the Act of Toleration of 1689 permitted certain congregations to worship in licensed meeting houses.

Recusancy

A year before the Gunpowder Plot, 'popish recusancy' was viewed as more dangerous than Puritan extremism.

…The Puritans (whose phantasticall zeale I mislike) though they differ in Ceremonies & accidentes, yet they agree wth us in substance of religion, & I thinke all or the moste p[ar]te of them love his Ma[jes]tie, & the p[re]sente state, & I hope will yeild to conformitie. But the Papistes are opposite & contrarie in very many substantiall pointes of religion, & cannot but wishe the Popes authoritie & popish religion to be established. I assure yor honor it is highe time to looke unto them, very many are gone from all places to London & some are come downe into this country in great jollitie almost triumphantlie… From a copy letter from Dr Matthew Hutton, Archbishop of York, to Robert Cecil, Viscount Cranborne, 1604 (Cl LP/14)

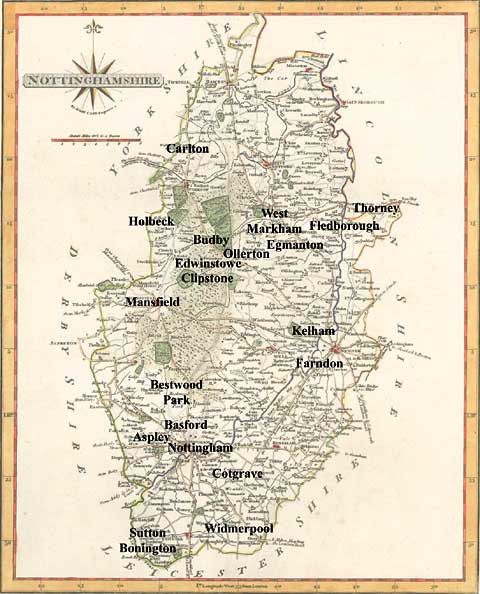

Accused recusants might be elderly people making an individual stand for the old religion, such as Amy Widmerpool of Widmerpool, said to be at least fifty in 1607, who was presented regularly until 1628. By contrast, some areas in Nottinghamshire were identified as Roman Catholic communities, usually centred around substantial families. This map shows the main locations of Roman Catholic activity in the period 1600-1643.

County map of Nottinghamshire by John Cary, 1793, marked up to show prominent Roman Catholic communities in the early 17th century from Bre 20

The Molyneux family of West Markham was one of the principal recusant families in Nottinghamshire, first appearing in the court presentments in 1608. Rutland Molyneux, accused almost annually until 1641, was said in 1625 to have had his child secretly baptised by a seminary priest.

Leaders of recusant communities were often members of old gentry families, whose servants were commonly accused with them for not attending church. In one bill, Rutland Molyneux's household is listed as including 'Blacke Elizabeth', who was perhaps descended from African slaves.

Protestant Dissent in the early 17th century

The presentment of people for attending services and sermons in other churches, and for repeating sermons without authority, indicates the spread of religious doubt and questioning.

William Brewster ['Bruster'] (c.1565-1644) was one such Puritan, looking for greater simplicity and zeal in religious worship than he found in the Anglican Church. His house in Scrooby became the location for a Separatist church led by John Robinson.

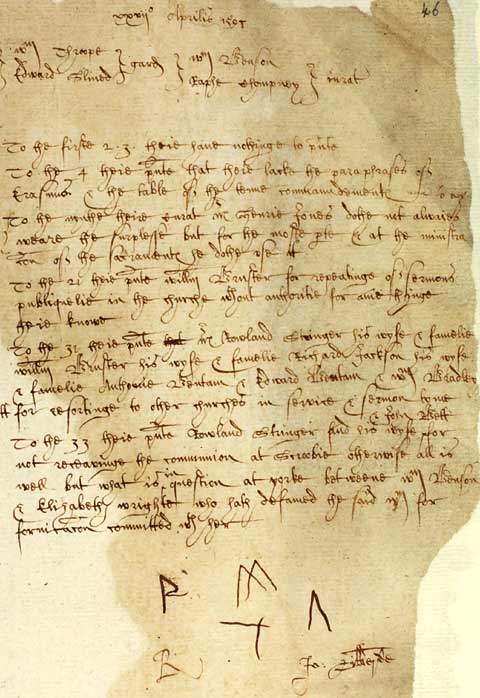

In 1608 the members of the church sailed for Amsterdam. Brewster sailed to Virginia in the Mayflower in 1620, as part of a group known to history as 'The Pilgrim Fathers', and helped to found the town of Plymouth in Massachussetts. The Presentment Bill below includes a presentment of 'William Bruster for repeatinge of sermons publiquelie in the churche w[i]thout authoritie for anie thinge theie knowe'.

Presentment Bill relating to William Brewster, Scrooby parish, 1598 from AN/PB 292/7/46

Thomas Helwys (c.1550-c.1616), a prominent Separatist, lived in Broxtowe Hall in the parish of Bilborough (now demolished). Presented in 1607 for not receiving holy communion, he moved to Basford before fleeing to Amsterdam with other members of the Separatist church in Gainsborough, led by John Smyth, and with members of John Robinson's church in Scrooby.

Helwys's wife, Joan, was arrested and imprisoned in York. Helwys later returned to London and founded the first Baptist church in England, where he was soon arrested. He probably died in prison, but his church lived on.

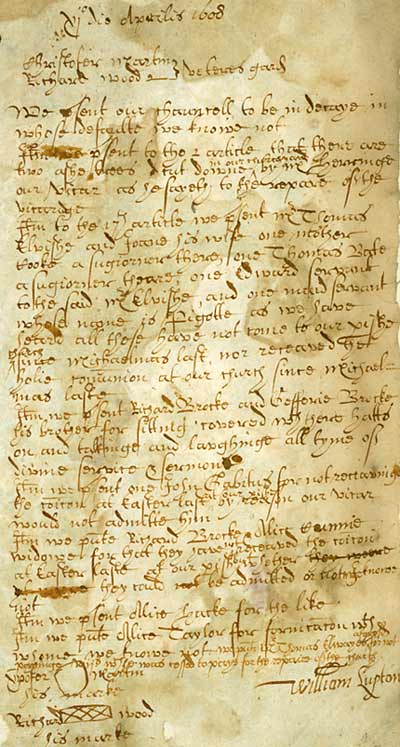

In the Presentment Bill shown below, from the parish of Basford, Helwys is presented along with a group of other Separatists:

'we p[re]sent Mr Thomas Elvishe and Joane his wife, one Mother Cooke a sugiorner [sojourner] there, one Thomas Bate a sugiorner theare, one Edward servant to the said Mr Elvishe, and one maid servant whose name is Pigotte, as we have heard, all these have not come to our p[ar]ishe church since Michaelmas last, nor receaved the holie com[m]union at our church since Michaelmas laste'.

Presentment Bill relating to Thomas Helwys, Basford parish, 1608 AN/PB 294/2/100

Below is shown part of the only Presentment Bill naming Henry Ireton (1611-1651), who as a Parliamentarian soldier in the Civil War rose to become Cromwell's lieutenant in Ireland. He was a regicide, one of those who signed King Charles I's execution warrant.

His parents, German and Jane Ireton, were frequent offenders in the Archdeaconry court. In 1616 German was presented for sitting in church with his hat on his head (a common Puritan protest against Anglican ceremony), and for having his child baptised without the sign of the cross. Jane was often in trouble for not mending Bramcote chancel, and not ensuring that her children attended church and catechism.

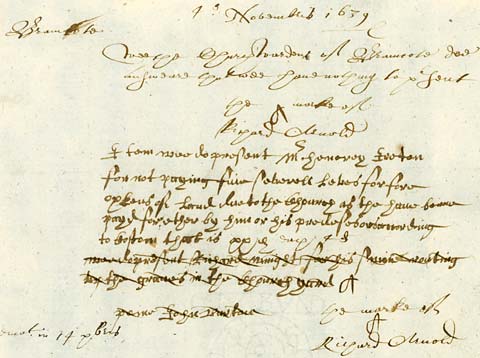

'Item wee do present Mr Henerey Ireton for not paying fiue severell leves for fore oxkens of land due to the chourch as the haue beene payd fore ether by him or his predesesors according to Costom that is xxd each 4d'.

('Item we do present Mr Henerey Ireton for not paying five several levies for four oxgangs of land due to the church, as they have been paid before, either by him or his predecessors according to Custom; that is, 20 pence, each one 4 pence'.)

Presentment Bill relating to Henry Ireton, Bramcote chapelry in the parish of Attenborough, 1639 AN/PB 303/679

Protestant Dissent in the later 17th century

The victory of the Parliamentarians in the first Civil War led to the abolition of the rule of the bishops in 1646. This allowed the establishment of local presbyteries and other religious groups such as the Society of Friends (Quakers). Their development during the years of the Commonwealth was to provide the origin for dissenting communities such as High Pavement Chapel in Nottingham.

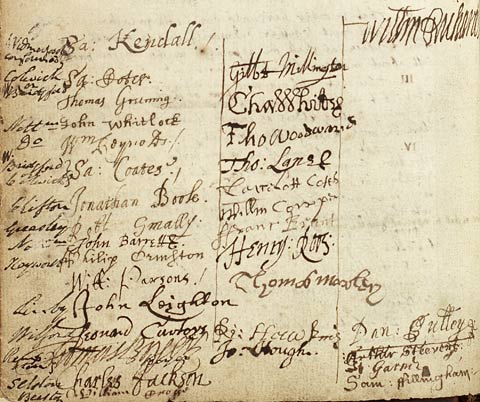

Many of the clergy identified below in the Nottingham presbyterian classis were ejected from their livings in 1662 because of their Presbyterianism. Some of the elders, listed in the second and third columns, refused to rejoin the Anglican church in the 1660s. Daniel Culley, maltster, Stephen Garner, apothecary, and Samuel Fillingham, tanner, came from the parish of St Mary in Nottingham and refused to take communion there in 1663. Elias Boyer of Rempstone, who was probably related to Thomas Boyer, minister there in 1656, was constantly in trouble throughout the 1660s for dissent from the Church of England.

Ministers and elders listed in the Nottingham Classis minute book, 1654-1660 Hi 2 M/1

Illustration of a Friends Meeting in the 17th century, from Cassell's Illustrated History of England, iii (London: 1864) from EMC Spec. Coll. Not 1.W8 HOW/W

Recusancy in the 18th century

Although the Archdeaconry Court was told about only one popish recusant at the Easter 1708 visitation, civil records show that there were many prominent Catholics in Nottinghamshire at this time.

Fears of a Catholic invasion of Britain were heightened in 1706 when James Francis Edward Stuart (1688-1766), the 'Old Pretender', son of the exiled King James II, attempted to land in Scotland as part of a French expedition.

As a precaution, the authorities in each county were asked to search the houses of known Catholics and non-jurors (people who refused to swear allegiance to Queen Anne), and retrieve any horses and firearms which could be used to support a rebellion. Resolutions of Deputy Lieutenants and Magistrates for apprehension of papists in Nottinghamshire, detailing the houses to be targeted, were drawn up in 1707 (Mol 29a).

However, none of the people named were brought before the Archdeaconry court for recusancy. Although the question of Catholicism was always asked of the churchwardens, it seemed they rarely answered it after the 1680s.

Next: Buildings and Bibles